Episode 2.1: The enchanted view of science

<Click image to enlarge>

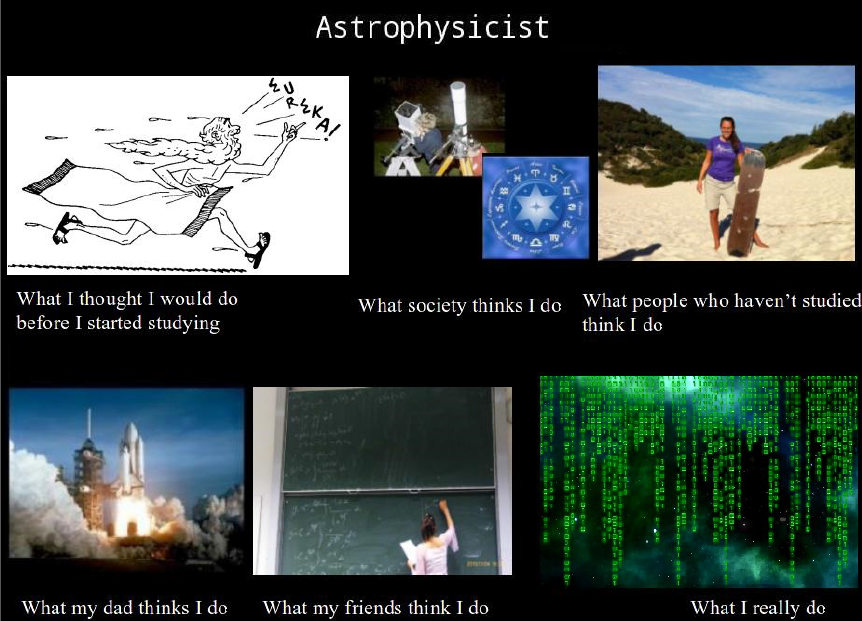

As described in the previous episodes, since I was 5 years old I wanted to become an astronomer to work on the biggest questions of the universe. As I was growing up I imagined how Einstein, Newton and Leibniz did science. I imagined them sitting in their office, being able to read everything there is written about their field, conducting experiments and developing formulas that add to that knowledge. Sometimes they would exchange their ideas through letters or at conferences. I imagined science as a peaceful process, just for the sake of gaining new knowledge. Historically, money didn’t play a big role, as those who could afford to do science were quite often those who were born into a wealthy family (so-called gentlemen scientists).

This is also what I imagined when I pictured myself in the future. I thought whatever is known about my field would be well summarised just like in popular science literature. The process of developing new knowledge would surely be even more efficient due to our new means of collaboration. I did believe that science represented an ideal community, a group of people sharing knowledge to reach the higher goal of uncovering new knowledge about how the world works. I assumed that science is intrinsically objective, cooperative and that it involves universal sharing of data and outputs. This is what the Science in Transition initiative describes as the “enchanted view” of science.

I believed in this view because in school we are only taught about what a genius Newton must have been to develop his law of gravitation, and not what an “asshole” he turned out to be. But I also believed in the enchanted view because most movies portray science as this cooperative endeavour that, after overcoming some dramatic moments, inevitably leads to Eureka moments. Now that I am a scientist myself I read newspaper articles about researchers discovering something super interesting with different eyes; I can imagine how many failures, struggles for research funding and feelings of despair those researchers must have actually gone through. But none of that is ever mentioned. Instead, the media lures the reader with flashy headlines, deluding them into thinking science has now found the unequivocal answer on how to cure cancer. The media perpetuates the myth that science is “the only place on Earth where completely disinterested and exaltedly inspired people are making the most beautiful discoveries” (– Science in Transition).

The following table compares some of the enchanted view’s beliefs to how science really works:

| “Enchanted” view | Science in real life |

| True science offers security and guarantees indisputable knowledge. | Even in science, there are no unequivocal answers, nor can science supply absolute certainty. Scientists are humans, neither infallible nor holy. |

| Science is faultless in identifying valuable scientific ideas. | Science is considerably more disorganised than is often thought. Scientists often have very different opinions among themselves and compete with each other for research funding. |

| Science is the only place on Earth where completely disinterested and inspired people make the most beautiful discoveries. | In reality there is competition for the best jobs (at prestigious universities), grants and awards. Scientists as human beings need to feel valued through recognition and publishing in “top” journals. |

| Nobody aspires to become a scientist for the money. | That is probably true. However, researchers are not exempt from life and are not financially independent “gentlemen” anymore: “Notwithstanding the beautiful aspects, science has become a normal profession, with a normal remuneration on which researchers are wholly dependent. Researchers are not exempted for life, and are not financially independent gentlemen if ever they were.” (– Science in Transition) |

Today, we are finding ourselves in a facts versus fakes crisis. In this view which opposes the enchanted one, scientific knowledge is often treated like Trump’s fake news. I have not committed myself to writing this article, or this whole series, to pour oil into this fire. My intention is not to support arguments that science produces fake news. Science is important for everyday life. It forms the basis for everyday items. It has a big influence on technology development. Scientific data forms the basis of policy making. Science is a central part of our philosophy of life, without which we cannot accurately interpret the world around us.

There is no field of human endeavour where science does not have a say. That is why it’s important to #Saywhatis by giving insights into how science really works. Understanding what culture and resourced are needed to perform good quality research would help the public and policy makers to support the scientific collaboration of bright minds. That is the purpose of this series “Science Backstage” and the reason why we need more science communicators who can translate scientific knowledge in a way that it becomes useful for us as the public, without giving us false hopes of being able to perform miracles. The public needs to regain trust in science and the first step towards that is being honest.

“Science is a human effort, but a very creative and special effort, because through science we can change the world. A successful demystification of science takes the researchers back in the public sphere where they belong, in the midst of potential users of new knowledge. Such a knowledge offensive would eventually only increase the involvement of the public, of politics but also of business.”

– Science in Transition

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 23rd June 2022