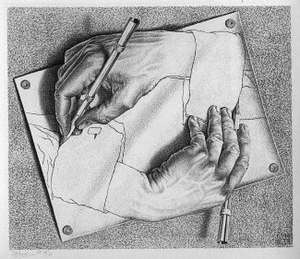

Reflexivity

Feedback loops of (self-) reflection and of social structures & processes on our behaviour

At school, I played along the numbers game without being aware of it. I believed getting good grades would pave my path of becoming an independent astronomer. Moreover, I recognised that defining whether a day was a successful one through intangible concepts, such as how much fun I had that day, is rather difficult. Measuring my success by the grades I received seemed to make more sense and give me more alleged certainty about being a worthy member of society.

How much does a grade really reflect on the knowledge or skills of the graded person with respect to a particular subject? And how much of it is knowing how to play along the rules of the game; anticipating what will be asked for the test and bulimic learning. I think my 15.5-year-old stepson is not too far off with his disappointment in schools that they focus more on teaching how to score good grades than teaching how valuable and enjoyable taught knowledge could be for life. Children are naturally curious and creative and, arguably, our schools quench this craving for knowledge and creation by stigmatizing mistakes and measuring education in grades from A to F (US), 1 to 6 (Germany) or 10 to 1 (The Netherlands). Playful acquisition of knowledge and experimentation becomes replaced by a target: getting a good grade.

Do you remember what Goodhart’s Law says about numbers that become targets?

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

– Goodhart’s Law

In other words, metrics are reflexive.

What is reflexivity?

In short, if something is reflexive, it means that its existence has feedback effects on itself and the context in which it is embedded. This glossary article is an extract of my PhD thesis and provides a definition of the concept of reflexivity.

First, I distinguish between reflection, which is an action, and reflexivity, which is a characteristic of (social) structures, processes and systems[1].

Second, reflexivity entails the acceptance of the ambiguity of our social and cultural world; for every subject, object, and situation there are usually more than one accurate possibilities to describe them[1]. Pluralism is accepting the co-existence of this various perspectives, which may even be contradictory. Moral relativism and deliberation of these various perspectives are fundamental to a democratic society. Reflexive knowledge is knowledge that entails knowledge about itself – about the context of its formation, its particular perspective and therefore its boundary conditions[1]. Reflexivity therefore acknowledges that knowledge is uncertain, context-dependent and ambiguous. Note that the relativity of knowledge (epistemological relativism) does not equal a relativity of truth (cognitive relativism).

“Reflexivity is a sceptical, Socratic, epistemological and critical attitude, but opposing fundamental relativism.”

– [1: p.21]; translated from German

Third, (self-) observation/ assessment is reflection that bares the potential of reflexivity when paired with the ability to learn from this reflection. Hence, when reflection goes beyond mere analysis and shapes what is being analysed, reflection is a reflexive performance.

Fourth, social institutions and processes, such as (self-)assessments, co-constitute actors’ behaviour – whether they are aware* of this feedback-loop or not[1,2]. Therefore, next to feedback effects, we speak of constitutive effects[3] when referring to the reflexivity of such processes. When there is no awareness of the involved actors, we may also label these effects as unintended consequences. An example would be the decrease of curiosity and creativity in children when they are taught to hunt for the good grades. Most of the times, the term unintended consequences comes with a negative connotation; we use it when we refer to effects we do not appreciate. However, be aware that all three related terms – reflexivity, constitutive effects and unintended consequences – are value neutral. Our (social) structures & processes may bring about aspired or not-aspired consequences. Bringing reflection back into the equation raises awareness about the shaping potential of social processes. With this awareness, the constitutive effects of reflexive processes may be capitalised to continuously learn from, such as in agile work environments.

* Moldaschl (2010) only characterises processes as reflexive when the acteurs, whose behaviour is being shaped as a result, are aware of it. Otherwise, he denotes them as “recursive”. I won’t make this distinction in order to be congruent with studies, which my dissertation is based on.

References [1] Moldaschl, M. (2010), “Was ist Reflexivität?”, Papers and Preprints of the Department of Innovation Research and Sustainable Resource Management (BWL IX), Chemnitz University of Technology, [2] Beck, U. (1986), “Risikogesellschaft - auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne”, Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp. [3] Dahler-Larsen, P. (2014), “Constitutive Effects of Performance Indicators: Getting beyond unintended consequences”, Public Management Review, 16:7, p.969-986

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 26th March 2024