Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

The last episode covered how we get from our situation to an action and how most of the times these actions are oriented around scripts and institutional norms. When we act in compliance with such institutional norms, we show normative (or norm-compliant) behaviour, which generally reduces the cognitive burden of our decision-making. This episode digs into the (perhaps more interesting? 😉 ) deviant behaviour.

“Deviant behavior is defined as actions that violate social norms, which may include both informal social rules or more formal societal expectations and laws.”

– Elizabeth Hartney (link); psychologist, professor, and director of the Centre for Health Leadership and Research at Royal Roads University, Canada.

When do we “misbehave”?

The short answer: When we disagree with the norm at hand and the projected sanctions for not following the norm not as bad as compared to the projected loss for following the norm, we may shift from compliant to deviant behaviour.

For the more comprehensive answer, let’s take a look back to the functions of institutional norms: The mere idea of the existence of a legitimate orderliness defines the meaning of behaviour in a specific cultural setting[1]. Meaning is introduced by institutions (i.e. meaning is socially constructed), and functions as the internal anchor of an institution. By setting the rules of the game and endowing behaviour with meaning, institutions structure expectations, interests and evaluations of actors. They direct behaviour by defining what is good or bad behaviour, what is right or wrong. Those actors who subjectively agree with the institution, its norms and what it represents, support the internal anchor and thereby legitimate the institution. Actors who do not agree with that specific institution do so, because they were socialised differently or decided to follow different, often contradicting, norms. For those actors, an institution needs an external anchor in the form of enforcement mechanisms like sanctions in order to make them follow the rules. However, when the absolute value of the gain from deviating from the norm is higher than that of the loss, actors will choose not to follow the norm. In other words, we will deviate from the mode of normative behaviour, when that deviation has a higher utility.

How do we “misbehave”?

Strategic behaviour

There are the more simple one-time deviant actions where we suffer the consequences or get away with it. Take the example from episode 1.1, where crossing the street at a red light as a pedestrian may have no consequences when no one is around and may bring a fine when a policeman sees you. We can probably find many examples for these kind of “minor” deviations in our daily lives.

It gets more complicated with long-term deviations. Resistance against a political regime, for example. Or “gaming” a performance measure. These kind of long-term deviations need a good strategy to be successful and in order to avoid the potential sanctions as much as possible.

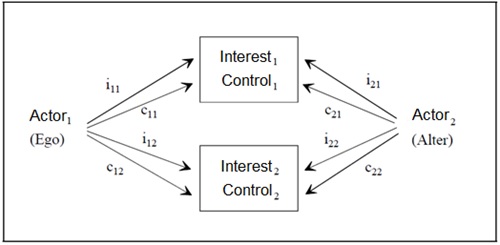

Often long-term deviations have something to do with the control over resources. The fact that resources are usually limited and that control over them is assigned according to the rules of the institution leads to a material bond[2] between actors (and the institution). Fig. 1 illustrates such a material bond by depicting a situation where two actors have a certain interest and at the same time exercise as certain control on two resources. The presence of such a material bond implies that actors need to employ strategies in order to maintain or gain control over resources. The scarcer the resources, the more efficient need to be the strategies. Any kind of strategic behaviour can be described and explained in terms of game theory[2].

Thereby strategies are rules about actions, available for a player/actor in a certain situation in a specific game/situation. Strategies themselves, according to Esser[2] are not actions, but roadmaps that determine actions as re-actions towards the actions of another player.

Strategic behaviour is not necessarily deviant, however. So when does deviance enter the game?

Anomie

Merton[3] refers to anomie as a useful concept to explain how actors adapt to or deviate from the present norms. Anomie occurs when there is a dissociation between how to legitimately meet personal or cultural goals and institutional norms. Institutional norms prescribe the institutional means, which are the ways or resources with which one can legitimately reach one’s goal. The dissociation between goal attainment and legitimate way of doing so may occur either because it isn’t clear what institutionalised means are necessary to reach the goal or because the resources are limited in a way that (some) people simply don’t have enough resources to meet the requirements set by the institutional norms. In either case, anomie weakens the internal anchor of institutional norms and deviant behaviour becomes more attractive. Merton defines five behavioural patterns one may adopt when there is an anomie:

- Conformity: One focusses on those goals, which are attainable with the available resources and under compliance with the institutional norms. Decision making happens in the mode of normative behaviour and doesn’t involve much reflection, leading to behaviour according to scripts.

- Innovation: One uses non-institutionalised means in order to attain (cultural) goals, either because the required capital is lacking, or because institutionalised means are regarded as inefficient. This behaviour may be frowned upon at first, but later it may be acknowledged as innovative. This pattern requires the mode of reflection and deviation from scripts.

- Ritualism: Bone-headed use of institutionalised means, ignoring possible negative consequences and neglecting cultural goals. This pattern displays a truly normative behaviour and doesn’t involve any reflection whatsoever, but is a stubborn execution of scripts.

- Retreat: Giving up in trying to meet cultural goals with institutionalised means that an actor (perceives themselves as) withdrawn from (e.g. drug addicts, dropouts from school/ society, etc). This decision may happen through the mode of reflected, rational acting or affect-driven behaviour.

- Rebellion: One rejects cultural goals and institutionalised means in favour of a new, socially not-approved system of goals and means. Like retreat, one may display this pattern through reflected and rational, or through affect-driven behaviour.

Note: Anomie is closely related to the psychological concept of cognitive dissonance. While an anomie is a dissociation between the cultural goals and the institutionalised means, a cognitive dissonance may occur when an actor experiences any clash of pieces of information or values – whether normative or not.

– Anomie versus Cognitive Dissonance

Deviant behaviour can therefore also be viewed as a sub-set of innovative behaviour.

Gaming the target

An especially interesting form of deviant behaviour is gaming a performance measure. We all know examples of this: buying likes on Instagram in order to appear more popular. Moving the mouse every 10 minutes in order to pretend that we working from home office, while actually doing our washing. Salami-slicing content in order to have more output.

Gaming directly targets the measure. While the initial idea is that the higher appeal an Instagram account has towards the outside, the more followers it gets. Therefore, we equate the numbers of followers with the quality of the Instagram account. Let’s say we want to become an influencer and can only do so with a follower number of 1 million. Now we can either do this by ways of institutionalised means; publishing content regularly, possibly also on other platforms with referral to one’s Instagram account. This, however, may be a slow process and we may feel tempted to take a short cut by buying some followers. The initial equation “quality of Instagram account = number of followers” does not work out anymore. This is because metrics are reflexive – they shape our behaviour. Or, in other words:

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

– Goodhart’s Law

Deviant behaviour – the unintended consequence of performance measures

Voila – we arrived at the unintended consequences (e.g. fake follower numbers) of performance measures. The function of performance indicators is that they are quantifying quality – squeezing qualitative factors into quantitative numbers – in order to “objectify” the performance. That way, performances become allegedly objectively comparable and rank-able. Next, resources (e.g. a job promotion) can be distributed according to these rankings. Performance indicators turn quality into capital that counts, at the cost of any qualitative factor that is not mapped onto the measure. We need this capital in order to attain the resources/goal we aspire and it therefore becomes very attractive to game the target.

This sort of deviant behaviour – gaming the target – is so special, because it represents two of the five ways to cope with anomie: It is confirmative and innovative at the same time. In other words, gaming strategies shall give the appearance of compliance, while institutionalised means how to achieve the target are used in innovative ways, such as acquiring followers in a creative way (buying them).

Now I am curious – what examples for deviant behaviour do you have? Where have you experienced anomie and how have you coped with it? Please share in the comments below or via private message!

References [1] Esser, H., (2000), “Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 5: Institutionen“, Campus Verlag Frankfurt/New York, DOI: 10.1007/s11577-001-0112-4 [2] Esser, H., (2000), “Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 3: Soziales Handeln“, Campus Verlag Frankfurt/ New York [3] Merton, R.K. (1949), “Social Theory and Social Structure. Toward the codification of theory and research”, Free Press, Glencoe IL

Navigate through the episodes of the special theme The Science of Human Behaviour here:

Table of Contents

- Introduction to The Science of Human Behaviour

- Motivation: Research shows that there are 5 different types of motivation. Especially the aggregate forms – autonomous vs. controlled motivation – have a different impact on our well-being.

- Decision Making: Rational Choice Theory explains how we make our 35000 daily decisions and how social phenomena arise from our individual behaviour.

- Episode 1: From situation to action

- Episode 1.1: Institutional Norms

- Episode 2: Taking action

- Episode 2.1: Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

- Episode 3: Emergence of Social Phenomena

- Self-Organisation & Transformation: Synergetics – the meta-theory of order transitions – connects the natural sciences with the social sciences and explain what we can change and what we cannot.

- Synergetics-Dictionary

- Episode 1: Physical principles and basics

- Episode 2: The relevance of transformation

- Episode 3: The Agile Organisation

- Episode 3.1: The Synergetic Navigation System (SNS)

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 25th October 2022