Transcending the tension between Consequentialism and the Categorical Imperative

Philosophy is often a subject that people make fun of: Philosophising is sometimes viewed as crunching one’s brain over seemingly irrelevant topics with no practical outcome. While I perceive philosophy to be vitally useful to gain insight into our own ways of thinking and behaving, I recently had a thought which I think may explain part of why philosophy has this dusty reputation: Philosophy – as opposed to most other subjects we learn about in school or study at university – evolves only marginally. When we learn about philosophy, we read about Plato, Socrates, Kant & Co – all people who lived hundreds or even thousands of years ago and whose ideas have been built upon since. These newer ideas are mostly lost in some digitals drawers of students or published in academic papers which never seem to see the light of a school lesson. Learning about philosophy is as if we learned in physics class that the world consisted of the 5 elements instead of atoms, which, in turn, consist of quarks.

Utilitarianism is such an example. It refers to a philosophical concept, which was first systematically described by Jeremy Bentham (*1748 – †1832) and John Stuart Mill (*1806 – †1873). I am sure I am not the first person who comes up with this – and I am at this point admittedly too lazy to search through the jungle of academic papers – but I would like to build upon this concept and call it meta-utilitarianism. Why would I engage in such an effort? Because I have been a meta-utilitarian since I can think and even knew about this concept.

Assuming you haven’t already closed the tab and have faith in me that this isn’t just another dusty philosophy lesson, let’s start with looking at the original definition of utilitarianism:

“Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that determines right from wrong by focusing on outcomes [of actions & choices]. […] Utilitarianism holds that the most ethical choice is the one that will produce the greatest good [i.e. utility] for the greatest number [of people].”

– Definition of Utilitarianism

The fact that – in the original definition of utilitarianism – the focus is set solely on the outcomes of an action, and not on the choice of the means, makes utilitarianism a form of Consequentialism. Consequences are what matters when judging the ethical value of an action. The opposite of consequentialism is the Categorical Imperative, which determines an action as right or wrong, based on moral duty, without taking the consequences into account.

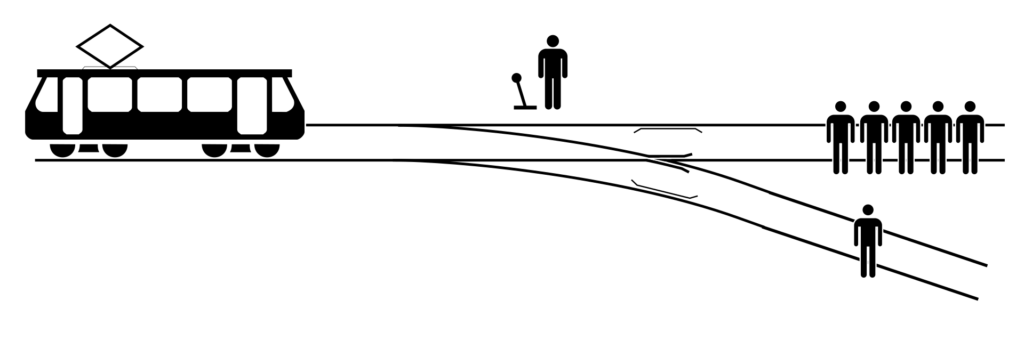

To understand the difference, let’s look at the famous Trolley Problem:

”The most basic version of the dilemma, known as “Bystander at the Switch” or “Switch”, goes:

– The Trolley Problem

There is a runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track. You have two (and only two) options:

1. Do nothing, in which case the trolley will kill the five people on the main track.

2. Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person.

Which is the more ethical option? Or, more simply: What is the right thing to do?”

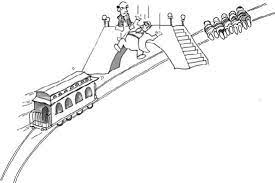

What pops up in your mind first with respect to what you would have chosen? Do you belong to the around 90% of people who would choose to kill the one person over five? Arguably, here the choice is rather easy (assuming none of these people mean anything to you). However, Harvard professor Michael Sandel illustrates that the choice becomes much harder if the problem is slightly modified: Suppose, you perceive exactly the same situation as before, but instead of coincidentally standing next to the lever, you find yourself on top of a bridge where the trolley will pass under in a moment before hitting the five people. There is no other track this time. Besides you stands a fat man (no body shaming intended) leaning over the railing. You know (suppose with absolute certainty) that if you push the man he will fall right onto the track and will will push the train off the rail. The man dies, the 5 people on the other track survive.

The consequences of the modified trolley problem are exactly the same as the ones from the original one: In making the decision to pull the lever/ to push the fat man over the railing, only one person dies instead of five. And yet – the number of people who would push the man off the bridge is significantly lower than those who would pull the lever. This modification exposes the difference between consequentialism and the categorical imperative; While the consequences (with respect to the number of people dying) are the same, we generally feel so bad about actively killing somebody that we choose the passive choice of letting four more people die.

This sort of dilemma – the tension between consequentialism and the categorical imperative – attracts the largest part of criticism against utilitarianism. At the end of the day, we are not just some kind of machines, which make an (instrumentally) rational calculation about how many lives to save. We are human beings and our feelings about the way we reach a certain outcome also matters, i.e. has an effect on us.

Transcending the tension between Consequentialism and the Categorical Imperative

Okay, now we can choose to whine about this dilemma and present it as such until the end of time or we can transcend it. This solution is pretty simple: Since our feelings towards the means we use to reach an outcome have an effect on us, why not factor these effects into the outcome, when we make the calculation what consequences our actions will bring about? This is actually what we do anyways already (consciously or not) when evaluating the consequences of our action. As described in the article on how we take action, psychological effects, such as the sunk cost effect, skew how we feel about the outcome. Voilà – the tension between categorical imperative and consequentialism is transcended. Now consider not only the benefit for yourself and others, but also the environment. This opens up a holistic view on the consequences of one’s actions. And this is what I call meta-utilitarianism:

“Meta-utilitarianism holds that the most ethical choice is the one that will produce the greatest good (value/utility) for the greatest impact on people and the environment.”

– Meta-Utilitarianism

So far so good. Since this was really a rather easy exercise, please don’t quote me on this, but rather find those academic papers which may already describe something like meta-utilitarianism. All I want to do with this article is to advocate for meta-utilitarianism, because I feel if more people valued the greatest good for the greatest impact, we would make less short-sighted and less selfish decisions. Suppose you figure you can take action A or B. Both cost the same amount of energy/ resources, but action B makes more people happy. Generally speaking, wouldn’t it make you feel better choosing action B? Suppose Action B included a small sacrifice for you, but a much bigger benefit for the other people – a utilitarian would still choose action B. A true (meta-)utilitarian does not do this based on some extrinsic motivation, but identified motivation – because it feels like the right thing to do. The value to maximise the greater good is integrated in a utilitarian’s motivational system.

Note that (meta-) utilitarianism is different to altruism:

“There exists a wide range of philosophical views on humans’ obligations or motivations to act altruistically. Proponents of ethical altruism maintain that individuals are morally obligated to act altruistically. The opposing view is ethical egoism, which maintains that moral agents should always act in their own self-interest. Both ethical altruism and ethical egoism contrast with utilitarianism, which maintains that each agent should act in order to maximise the efficacy of their function and the benefit to both themselves and their co-inhabitants.”

– Difference between altruism and utilitarianism; Wikipedia

Isn’t (Meta-) Utilitarianism too demanding?

The short answer is: No – Just do the best you can do considering the information you have and your (timely) constraints. The longer answer lies in the following paragraphs:

You may find (meta-)utilitarianism more appealing than altruism, because with the former attitude you also take your own interests into account. (Meta-)utilitarianism is less demanding than altruism, in that we do not need to deny our own feelings or desires. And yet, there is criticism that utilitarianism may be too demanding. First of all, our rationality is bounded, which means that our ability to make (subconscious) calculations of the consequences of our actions is limited. Second, in practice, we hardly have the chance to get perfect information to base our calculations on. Third, making sacrifices to increase the value for others may be exhausting in the long run.

However, raising these three points as criticism against utilitarianism begs the question: Is there a better alternative to utilitarianism? Is it better to act selfishly, because we won’t don’t have perfect information? Or isn’t rather the best choice a meta-utilitarian approach, where we just do the best we can with the information we have?

I argue for the latter of course. We need to make choices on how much we can afford to reflect on the consequences of our actions, our motivations and the psychological effects that factor into our decisions. We need to make choices on how much information we can afford to gather before taking action. In every decision, we make this trade-off.

Moreover, just like we need to find a good balance between instant and delayed gratification, we need to find a sustainable approach to meta-utilitarianism in order to not overdiscipline ourselves. If we do not want to burn out, we need to account for the fact that we need self-maintenance, for example, by occasionally doing something out of intrinsic motivation, regardless of the optimisation of the consequences of our decision making.

(Meta-)Utilitarianism & Agility

Finally, I argue that meta-utilitarianism is closely related to the value maximisation principle of the Agile mindset. Naturally, an agile organisation likely focusses on business value, however, there is an increasing awareness that customer value maximisation is not unrelated to employee satisfaction and sustainable (product) development. (Meta-)utilitarianism, just like Agile, is about an efficient & effective way to use resources to have the most suitable & sustainable outcome for everybody involved – the employees, customers and the environment. And just like (Meta-)utilitarianism, the Agile mindset involves “systems thinking”- a holistic/ systemic view on the situation we are facing.

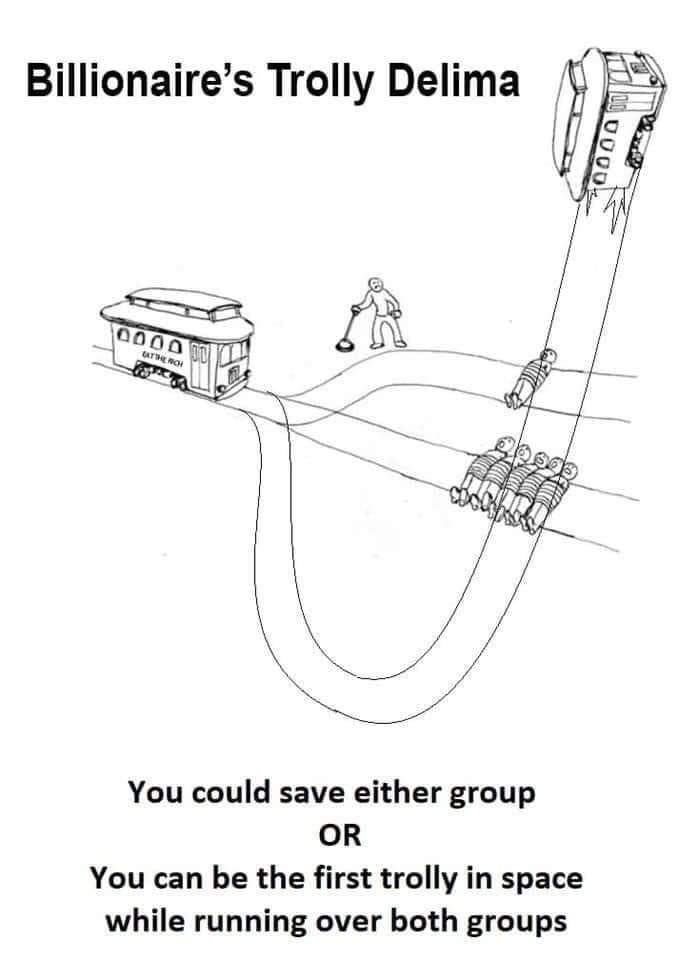

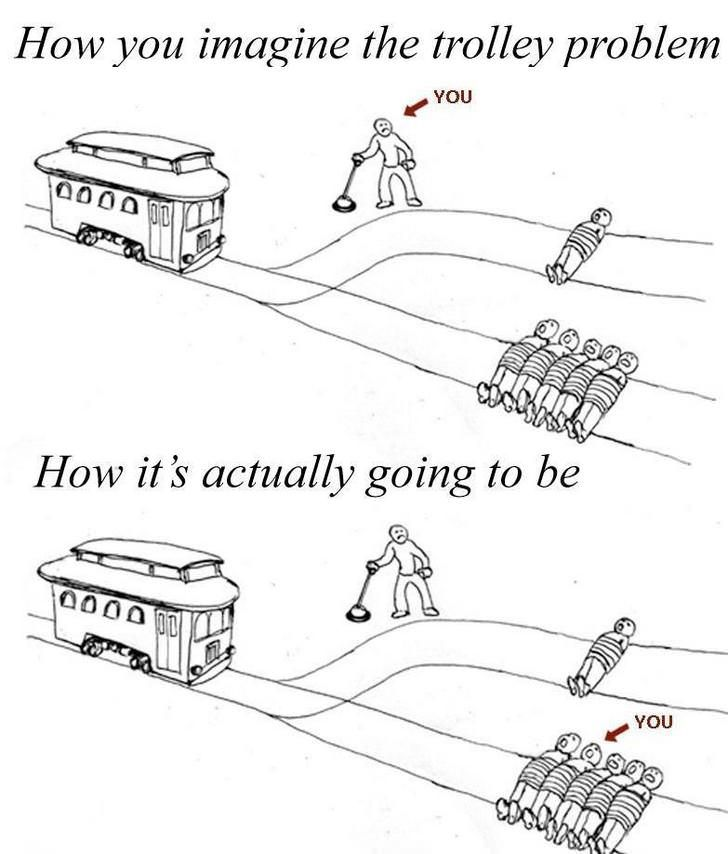

To close this philosophy article off with some fun, here are two more modified Trolley Problems for you:

What values govern your decisions? Do you take the consequences of your actions into account? Your feelings? The value your action brings to others? Does the meta-utilitarian idea resonate with you? I am curious to hear your reflections on this topic!

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 25th May 2023