5 Types of Motivation

I remember this situation at university, where my colleague complained to me that so many others haven’t done their homework, despite attending this course out of their own free will. And it’s true – probably nobody forced them – to attend this class, yet some voice at the back of my head asked: “But how free does everybody really feel in their choice to sit here today, after all?”

I was thinking about myself: Why am I sitting here? Certainly not because I was truly enjoying this particular boring lecture. Instead, the answer was that I wanted to become an astronomer. Participating in the hamster wheel of lectures, homework and exams was, for me, a means to an end to become a researcher in astronomy. So, am I sitting here based on my own choice? Yes, certainly, nobody is forcing me. Am I sitting here because I am enjoying it – most of the times not. I am here because I want go get something – the graduation certificate.

I certainly didn’t interview how my astronomy colleagues felt about their motivation to be present in lectures and to do or not do their homework, but I extrapolated a little bit and came to the conclusion that there are actually many things in life we do “out of free will”, but not because we really want to (it’s part of being an adult).

Finally, doing my PhD, which involved studying different types of motivations for becoming an astronomer and to publish scientific papers, I discovered the literature, which made it possible to differentiate between various forms of motivation. Because I love applying science to my daily (private) life as well, this literature has opened my eyes for why I do the things that I do. I feel that when we know out of which motivation we do certain things, we become aware of our true drivers and can more actively choose for or against them.

But first things first. Let’s dig into the types of motivations, before we discuss what we could benefit from that knowledge.

The conceptualization of motivation that I find most useful is rooted in self-determination theory (SDT[1-4]), which belongs to the domain of organisational psychology. SDT categorises types of motivation at two different orders of approximation. Put simply, an order of approximation is a zoom in; at higher orders of approximation, we zoom in more than on lower ones. A higher zoom results into more details, but less overview over the whole picture and the relations of its parts.

First order of approximation: Intrinsic versus Extrinsic Motivation

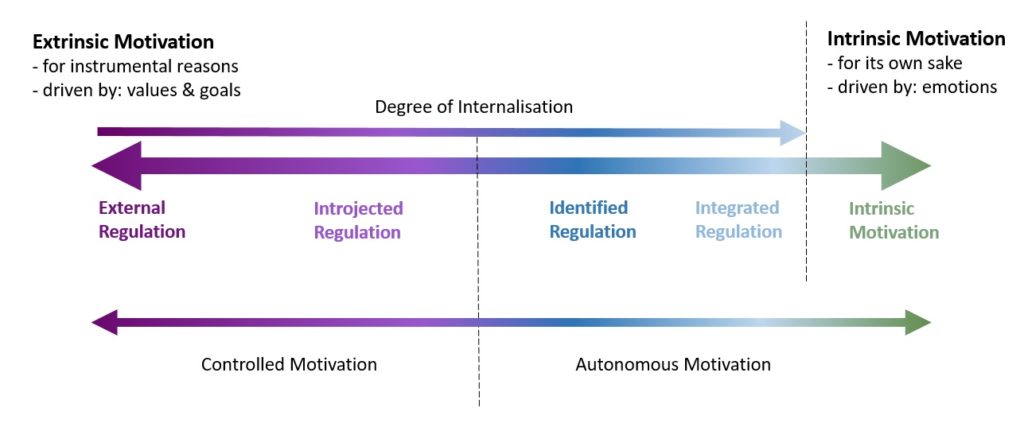

At first order of approximation, SDT distinguishes between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation – terms you have probably also already heard of. Motivated by extrinsic motivation, one engages in an action for instrumental reasons, whereas an action performed out of intrinsic motivation is done for its own purpose. That means that if we do something out of extrinsic motivation, we do it, because we want to get/ avoid or achieve something – the act is a means to an end. By contrast, if we do something out of intrinsic motivation, we are not focussed on the result, but truly enjoy the act. Extrinsic motivation is driven by values and goals, whereas intrinsic motivation is based on emotions, such as joy and curiosity.

Second order of approximation: The 5 types of Motivation

At second order of approximation, SDT distinguishes between 4 different forms of extrinsic motivation, next to intrinsic motivation. We may picture those four so-called regulations as a continuum (Fig. 1), depending on their degree of internalisation. Internalisation refers to the assimilation of a regulation with existing self-regulations, based on one’s values and interests. In other words, the higher the degree of internalisation of a regulation, the more does one identify with the value or meaning of the activity.

In the following, I’ll illustrate the 4 different types of extrinsic motivation with the example of helping a friend move house:

External regulation, the type of extrinsic motivation with the least degree of internalization, refers to doing an activity to obtain rewards or avoid punishments. This also includes rule-following, so doing something, because we were socialised to – for example, stopping at a red light. If we help our friend relocating mainly based on external regulation, we do so, because we, for example, expect the favour or a reward in return. In this case, we get pleasure from the anticipation of the reward.

Next on the spectrum, we find introjected regulation, which refers to “the regulation of behaviour through self-worth contingencies such as ego-involvement and guilt”[3: p.2]. We act out of introjected regulation to receive (self-)approval and avoid disapproval. Introjected regulation is based on assimilating a regulation in a way that it becomes internally pressuring, which means it is partially internalised, but remains controlling. When we help our friend moving house mainly based on introjected regulation, we do so, because we’d feel, for example, guilty or like a bad friend otherwise. In this case, we avoid the pain of feeling like a bad friend.

Identified regulation is almost fully internalised and hence one identifies with the value or meaning of the engaged activity. The goal that the activity poses is accepted as one’s own and as such has personal importance. Therefore, identified regulation is not controlled, but autonomous. The most autonomous and completely internalised form of extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation. It “refers to identifying with the value of an activity to the point that it becomes part of a person’s habitual functioning and part of the person’s sense of self.”[3: p.2] In practice, it is very difficult to distinguish between identified and integrated regulation, which is why I will drop the latter for now and only use identified regulation for my example: If we help our friend relocate mainly based on identified regulation, we do so, because, for example, we find it valuable to help a friend in need. In this case, we get pleasure by doing what we think is right.

Last, but not least, if we help our friend move houses mainly out of intrinsic motivation, we do so because we genuinely enjoy the act of packing boxes and loading them into the car. In this case, we get pleasure by the joy of the act itself.

As you may have noticed, in the examples of helping a friend relocate I wrote “mainly based on X motivation”. This is because, naturally, in practice one engages in an activity out of a mix of the 5 forms of motivation presented above (4 forms of extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation), with one of them at peak. In other words, when we say an action is motivated by, for example, introjected regulation, then this is the type of motivation that was most determining making the decision to engage in the action.

The aggregate: Autonomous versus Controlled Motivation

The 5 different forms of motivation proposed by SDT make sense from a theoretical point of view, given the different degree of internalisation of the regulations and that intrinsic motivation is the only form of motivation not based on instrumental reasons. However, in practice, we may not always be able to (statistically) differentiate within autonomous forms of motivation (identified regulation, integrated regulation and intrinsic motivation) and controlled forms of regulation (external and introjected). I illustrated the categorization into autonomous and controlled motivation also in Fig. 1.

Research has shown that there is a clear difference in the consequences of acting based on controlled versus autonomous types of motivation, so for many purposes these aggregates may be sufficient[3]. The next article in this series about motivation discusses these consequences – so what impact it has on us to act out of controlled versus autonomous motivation.

But first, I am interested in how this article has impacted you – does this categorisation of motivational types help you in determining the real drivers for your decisions? Does it help you to make decisions more consciously? How useful to you find applying these categories in your daily life? I am curious about your contemplations of this topic, so please do drop me a message or comment below 🙂

References [1] Deci, E. L.; Ryan, R. M. Intrinsic motivation and self determination in human behaviour. New York, NY: Plenum 1985. [2] Ryan, R. M.; Connell, J. P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1989, 57, 749–761. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.749. [2] Gagné, M.; Forest, J.; Gilbert, M.-H.; Aubé, C.; Morin, E.; & Malorni, A. The Motivation at Work Scale: Validation evidence in two languages. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 2010, 70, 628–646. doi:10.1177/0013164409355698. [4] Gagné, M.; Forest, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Crevier-Braud, L.; van den Broeck, A.; Aspeli, A.K.; Bellerose, J. et al. The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 2015, 24:2, 178-196, DOI: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892.

Navigate through the episodes of the special theme The Science of Human Behaviour here:

Table of Contents

- Introduction to The Science of Human Behaviour

- Motivation: Research shows that there are 5 different types of motivation. Especially the aggregate forms – autonomous vs. controlled motivation – have a different impact on our well-being.

- Decision Making: Rational Choice Theory explains how we make our 35000 daily decisions and how social phenomena arise from our individual behaviour.

- Episode 1: From situation to action

- Episode 1.1: Institutional Norms

- Episode 2: Taking action

- Episode 2.1: Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

- Episode 3: Emergence of Social Phenomena

- Self-Organisation & Transformation: Synergetics – the meta-theory of order transitions – connects the natural sciences with the social sciences and explain what we can change and what we cannot.

- Synergetics-Dictionary

- Episode 1: Physical principles and basics

- Episode 2: The relevance of transformation

- Episode 3: The Agile Organisation

- Episode 3.1: The Synergetic Navigation System (SNS)

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 30th August 2022