The simple answer is: Both!

Find the more comprehensive answer in this blog article.

Realism versus Constructivism?

As I described in the Introduction to the Science of Human Behaviour, I struggled for years with the question of whether there is a reality, independent of our perception or whether we socially construct our reality. Because I am trained as a natural scientist, I used to strongly favour the former – so-called realism – over the latter – so-called constructivism.

“A realist position sees the world as – literally – real and posits that we know what we know because of some inherent quality that things in the world have. By contrast, a constructivist approach sees reality as socially constructed: we know what we know because of social practice.”

– discourse.ch

Commonly, realists also believe in (ontological) reductionism. This is the belief that “the whole of reality consists of a minimal number of parts” and that a phenomenon can be explained by the underlying dynamics of these parts. Constructivists, by contrast, are often not interested in a causal explanation, but in explanations on phenomenological level. Which, by the way, usually make more sense in our daily lives as I describe in this episode on the emergence of social phenomena. It is, however, a good attitude for a scientist (or a curious mind in general) to assume reductionism – how else can we dig into the phenomenon and truly understand it?

Upon my switch to the social sciences, I had many fights with social scientists, who defended constructivism, while I argued that even the emergence of social constructs can causally be explained (just like physical constructs). A bit later I learned about synergetics – the science of self-organisation. This meta-theory explains how phenomena emerge from the dynamics of other phenomena – no matter the nature (physical or social). This way, synergetics bridges the gap between the natural and the social sciences – how exciting! With this scientific backup up my sleeve, I found peace with my rage against constructivism and could even get something out of this school of thought.

With my mind at peace, I realised it is not either realism or constructivism one needs to decide for, but both at the same time!

Realism *as well as* Constructivism!

Yes, I believe that there is a physical reality out there that is independent of our experience and perception, but now I also understand that any knowledge about it is socially constructed, informed in the light of our previous knowledge, biases, conventions and situated in the context of our culture.

How about the social reality, however? What actually is social reality?

Social reality comprises of “the institutions and structures that come to exist because of people’s actions and attitudes. These features of the social world exist because significant numbers of people act as if they do.”

– [1: p.58-59]

And how does physical reality compare to social reality with respect to being “real”?

An example are institutional norms – rules about how to behave and navigate our society. They are invented and perpetuated by humans and “have real effects because people act on them and act with respect to them”[1: p.59]. They prescribe behaviour. For example, money is a social construct. The physical coins and notes do not inherently possess the value we attribute to them. Only through our shared belief in our currency and the consequences that this belief has on our actions does money become such a real thing in our heads. And it is “real” – having or not having money has actual effects on us.

Example Gender: The heated debate – biological fact or social construct?

One current controversial subject is whether gender is a social construct (constructivism) or a biological reality (realism). Gender-critical people argue that gender is a social construct and that the binary definition of gender is too restrictive to represent the whole variety of gender-related differences in human beings. Others argue that gender is a biological fact. It simply comes down to your XX or XY chromosome pairs. Who is right?

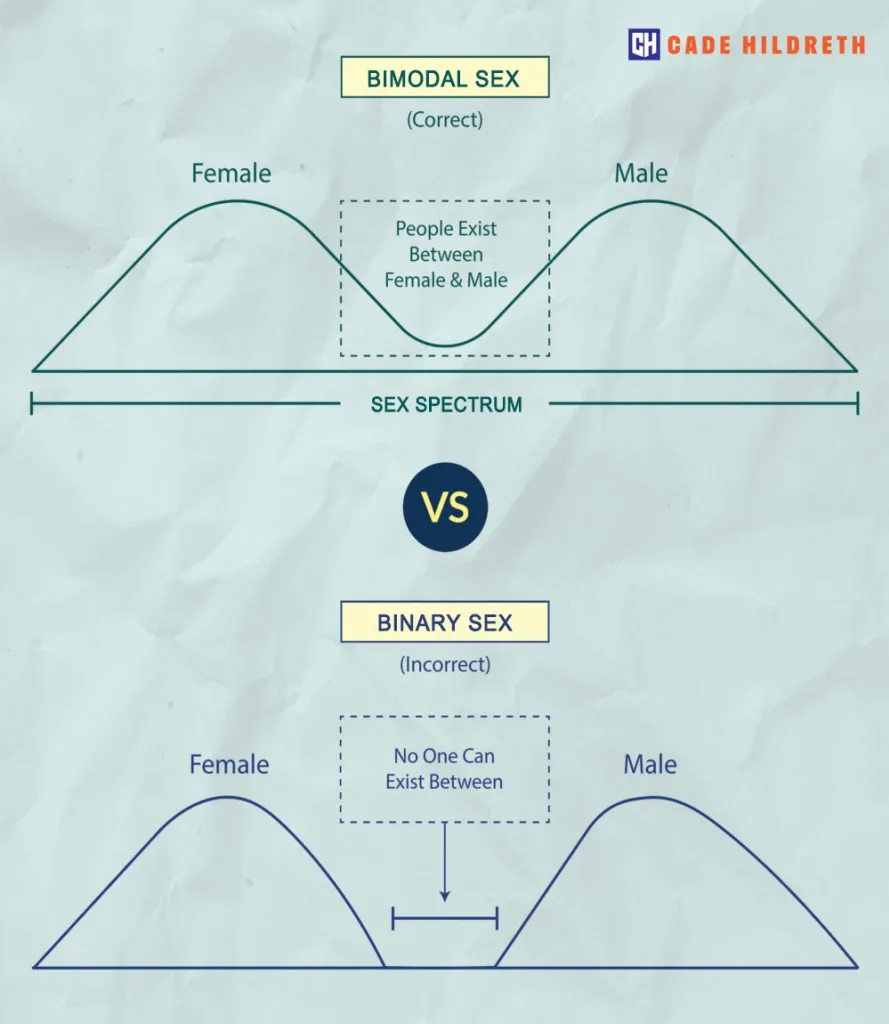

To answer that question, let’s first look at the biological aspect of gender (i.e. sex). Many proponents of the biological definition of gender argue that it’s a simple matter of whether having a penis or a vagina. Others dig deeper and look for the cause of genitals, and refer to the XX or XY chromosome pairs. However, to get from chromosome pairs to the formation of a penis a whole lot of biological processes – dependent on hormones, hormone receptors and enzymes –are involved. A variation of these lead to a whole spectrum of different – what we call female or male – characteristics. Moreover, there are more variations of chromosome pairs, such as XXX, XXY and XYY. In a nutshell, even the biological definition is complicated. As a consequence, many biologists do not talk about a binary sex anymore, but about a spectrum with male and female extremes. Therefore, sex characteristics tend to be bimodal and not binary[2].

Now let’s turn to gender as a social construct. Irrespective of any biological foundation of a gender, the labels we use in our society, together with their meaning, are a social construct and have real consequences.

“A social construct or construction is the meaning, notion, or connotation placed on an object or event by a society, and adopted by that society with respect to how they view or deal with the object or event.”

– Wikipedia

Let me give you an example for the value-ladenness of labels: In a discussion with my department head at the time I was doing my PhD at Humboldt University, he told me about this survey that asked people how many times they have cheated on their partner. I can’t remember exactly (the exact number is not the point here), but let’s say the average was 1.5 times. Now what may happen? Suddenly, infidelity is something that is talked about, something that has been assigned an average number. If 1.5 times is “normal” and I have “only” cheated once, is it then so bad if I cheat a second time?

The bottom line is that statistics do not only measure behaviour, but they also prescribe behaviour. The same goes for the labels we have. Classification systems are not neutral on the things that they classify. Squeezing people into labels has consequences:

“Gender structures create constraints and resources with which people have to reckon. As a result, treating people as gendered tends to create gendered people. Genders have causal powers, which is probably the best sign of reality that we have. At the same time, they are undoubtedly not simply given by nature, as historical research and divergences between contemporary cultures show us.”

– [1: p.59]

Reconciling the physical reality with the social realty

Does this mean that we should abandon the gender label all-together, because it is biologically ambiguous anyways and seems to not accurately reflect how people feel about their gender? In my opinion, the answer lies in ambiguity tolerance and the question of contextual relevance of the gender.

For example, biologically a tomato is classified as a fruit – a label which may have some relevance for genetic research and tomato growers. However, in our daily lives we do not treat it as a fruit. The biological label has no relevance for us when we consider whether or not to put a tomato into a fruit salad. Therefore, we acknowledge the ambiguity of the tomato label by recognising it as a biological fruit, but not forcing it into a fruit salad.

The same goes for the gender label. Depending on the context, it may be important what kind of genitals one has, e.g. when it comes to medical topics. Cancer risks, for example, depend on hormones and genitals. In our search for a suitable mate, it may be important to us to find the binary opposite of our sex. By contrast, in our society, we do not want our genitals to be relevant for whether or not we can attend a public event (cf. equality), so why squeezing our gender identity into a binary label in an RSVP form?

If we, therefore, develop an ambiguity tolerance for the plurality of sex traits based on biological processes on the one hand and social identities on the other hand, we do not need to deny the importance of one or the other any longer. We would recognise the importance of the biological sex where it is relevant (e.g. medical questions) and would at the same time recognise the importance of social gender identity. This comes with developing an awareness of the consequences of labelling people.

Therefore, I agree with the following conclusion:

“Biological processes are facts – the labels that we assign to them are not. Our labels are the result of our culture, which arises from a certain context. […] Naturally, gender is about much more than what biology can measure. Nevertheless, it’s not detached from biology.”

– Franca Parianen, neorosientist; translated from German

In short, gender is a biological fact1 and a social construct. Whether it’s best to refer to one’s biological sex or gender identity depends on the relevant context.

The English language has actually resolved the ambiguity of biological fact versus gender identity by distinguishing between the two terms sex (biological traits) and gender (social construct). However, these terms are still often used interchangeably in ordinary speech and many other languages do not make this distinction. This is why it is still so important to emphasize the potential ambiguity of the gender label. Next time we argue whether something refers to a (biological/ physical) fact or to how we perceive it, we may choose to tolerate the ambiguity and potentially resolve it by creating new labels.

Now, since this is such a hot topic, I invite you to share your experiences with regards to gender (label) –respectfully – in a comment below or in a private message!

1 Although also not as unequivocally binary as we may think, but probably more bimodal.

References [1] Sismondo, S. (2010), “An introduction to science and technology studies”, 2nd ed, ISBN 978-1-4051-8765-7 [2] Hildreth, C.(2022), “The Gender Spectrum: A Scientist Explains Why Gender Isn’t Binary”

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 24th October 2022