Rational Choice Theory: Emergence of Social Phenomena

Have you ever wondered how social phenomena, such as friendships, organisational culture, revolutions or wars, emerge? Rational choice theory (RCT) – my broad-spectrum medicine to understand all sorts of human behaviour – can explain it!

The Chicken and the Egg: Macro versus Micro

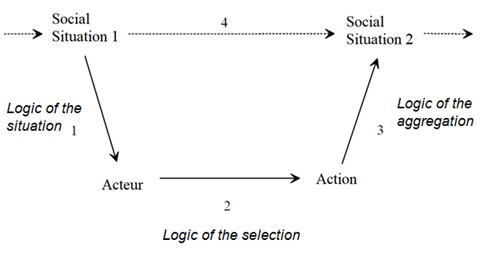

(modified by me, based on [1])

Rational choice theory is a sociological theory of action, which explains how macro phenomena emerge out of micro phenomena and how, in turn, they can influence micro phenomena[1]. Now, what the hell are micro and macro phenomena? These are relative terms. A macro phenomenon comprises micro phenomena and spices them up with some dynamics. Water drops, for example are a relative micro phenomenon compared to the macro phenomenon of a wave that they can cause. In a social situation, we often picture individual actors (humans) as the micro phenomena and the social phenomenon that they cause by acting collectively, as the macro phenomenon. The emergence of a macro social phenomenon from individual actors making decisions, is illustrated by the so-called Coleman Boat[2] (Fig. 1).

When we want to know how a social situation arose, we have two options: First, finding an explanation on the phenomenological level (step 4 in Fig. 1) or second, finding the causal explanation by looking at what happened on a lower level. For example, a revolution (Social Situation 2 in Fig. 1) may be explained by the severe suppression of the citizens up to the point where they found the threat of the sanctions less scary than the prospect of gaining some freedom (Social Situation 1 in Fig. 1). Such explanations on phenomenological level are most of the times sufficient. They are a useful shortcut by only looking at what’s directly relevant to explain the resulting macro phenomenon. However, they are lacking an explanation of the true causal mechanisms that lead up to Social Situation 2. This is necessary if we want to truly understand what was going on a deeper than surface level.

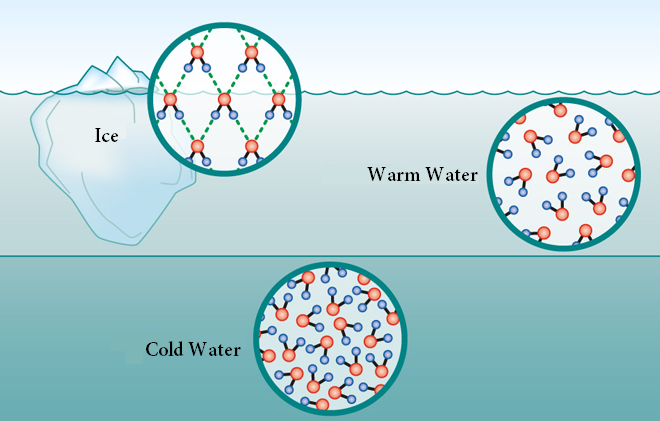

Source: © maribus

Another example from daily life: When you say: “I am going to drink a glass of water”, people will understand what you mean, even though you are talking about a process on phenomenological level. You basically dumb the process down, strip it off its molecular and physical complexity. For a physicists or chemist, on the other hand, it may be interesting to look at what’s really going on the more microscopic level: the structure of the H2O molecules that are trapped in a structure of whatever glass is made of. In our daily lives, we do not need to waste any mental energy on thinking about thousands of H2O molecules and their physical orientation towards each other, it’s sufficient to talk about water (ice).

Take this even a level deeper: the properties of water (H2O) cannot be explained by combining the individual properties of oxygen and hydrogen. On phenomenological level an early chemist may have observed that these 2 elements can form an H2O molecule showing additional emergent qualities, which 2 hydrogen and 1 oxygen atom would not display without that molecular bond. To really understand how these properties can come into being, we needed physicists and chemists to analyse chemical reactions and atomic properties. They needed to look below the surface of an atom. Now that we have that theory, we can just apply it and talk about the process of an H2O molecule forming without going into the details of the quantum mechanical processes that are going on backstage.

Below the surface: How the egg caused the chicken, caused the egg …

Enough talk about explanations on phenomenological level – as a scientist I am naturally interested in what’s really going on below the surface. And RCT can deliver such causal explanations about how one social phenomenon led to another. It does so in 3 steps (Fig. 1).

- Reconstructing the 4 constituents of an actor’s situation results in the logic of the situation; the reasons for an action. This is the first step in finding a sociological explanandum for the resulting macro phenomenon. We discussed this step in the first RCT episode, but here a short summary: According to RCT, not only the prevailing culture, including its (institutional) norms, but also the present material opportunities/resources, and personal motivations comprise an actor’s situation[1]. Institutional norms set the rules for what is appropriate behaviour and define what are desirable goals. Personal motivations are part of the so-called internal component of an actor’s situation, while culture, norms and material opportunities make up the 3 external components. The actor’s situation influences their decisions and hence their behaviour.

- The second step is analysis the logic of selection. In other words, how does one select between action alternatives, based on one’s situation? First we need to find bridge hypotheses, which translate the logic of the situation into the variables that the actor’s behaviour can depend on. These bridge hypotheses link the objective situation of an actor to their subjective motives and knowledge. This means that an actors’ subjective goal is based on their internal values wishes and oriented around the objective material, institutional and cultural situation. In order words, bridge hypotheses link the situation of an actor to their resulting behaviour. Bridge hypotheses explain the actor’s motivation for an action. An action theory is now needed to explain the action on the basis of those variables. We discussed my favourite action theory (EU-theory) in the previous episode, which also includes an example for choosing between 3 action alternatives.

- The final and third step is to find transformation rules which explain how the individual actions of many actors aggregate to the sociological phenomenon in question. This step is also called the logic of aggregation. The result is a sociological explanation of how one social phenomena causes another, by reconstructing the causal mechanisms, which happen on a micro-level relative to the macro-level of the collective phenomena. Hence, exercising all 3 steps delivers a causal explanation for how Social Situation 1 leads to Social Situation 2, which otherwise could only be observed and described on a phenomenological level (step 4 in Fig. 1).

Note that there is no claim on what was first – the chicken (macro phenomenon) or the egg (micro phenomenon). We are dealing with a so-called circular causality, where macro and micro phenomena influence each other. Micro phenomena cause macro phenomena, however, those micro phenomena themselves where previously influenced by some macro phenomena. We are basically dealing with a never ending chain of nested Coleman Boats, drawing back all the way to the Big Bang.

An example: The formation of friendship

Since the 3 steps may have come across as a bit dry and too theoretical, let me illustrate the causal explanation according to RCT with an example: the formation of a friendship[3: pp.14-18].

In essence, friendship <F> is a relation between two (or more) previously (in this respect) autonomous actors. This relation is generally based on some kind of co-orientation <f>, for example some kind of shared meaning, such as bonding over hobbies, being a parent, having the same goals etc. The first condition for a friendship to emerge, is meeting; the two people need to meet first. For this, they need opportunity structures, such as school, university, parties, kindergarten, tennis club, etc. The second condition is mating; they need to have some kind of shared meaning, attitude, goal, denounced as f.

The logic of the situation is mostly determined by the opportunity structures to meet (material opportunities, cultural frame) and the individual personalities of the two people. The bridge hypotheses assume that if both actors are similar in certain aspects of their internal component (personality, wishes, values, goals), the expectation to experience more pleasant encounters with each other will rise. The two people will act on that expectation if the expected utility (benefit) of meeting each other has a positive result. Now we are at a stage of occasionally meeting and sharing positive experiences with each other. Is that friendship yet? Not quite, we are still at the stage of friendship formation – two autonomous actors who are acquainted with each other. To explain how the social phenomenon of a friendship arises, we need a transformation rule. An appropriate transformation rule could be: the collective phenomenon friendship <F> between two actors A & B emerges when both actors agree on their attitude <f> and when <f> co-orientates both in their actions. In other words, that shared value, goal or hobby <f> bonds them together and makes them make decisions together, whereas before they would not have taken the other into consideration. A social phenomenon friendship emerged, including some kind of mutual co-dependency of previously autonomous actors.

An example: Why we believe in norms

Another example is the organisational, orientational and meaning function of institutional norms, that we discussed in a previous episode. As we learned from that article, it is the very purpose of institutional norms to be followed without questioning in order to guarantee smooth interactions between actors and for the actor to reduce the cognitive effort decision making would otherwise cost. In other words, the whole purpose of rules is to organise people’s behaviour and orientate them towards certain goals. How does that work in RCT parlance?

An actor finds themselves in a situation with certain institutional norms. The actor evaluates that it brings a better expected utility to display normative behaviour (to comply with the norm), because the sanctions of deviation would be too high and/ or because the actor internally agrees (meaning function) with the rule. If most actors would come to the same conclusion, the institution gains legitimacy and fulfills their functions. How do we get from a lot of individual actors to the collective phenomenon of organised behaviour? Through institutional norms collective social phenomena come into being, simply because they prescribe certain social processes that follow from an individual’s situation. The transformation rule then amounts to assuming regularity of those empirical social processes, which are treated as a logical consequence from institutional norms[1].

RCT – An application of the Meta Theory of Transformation (Synergetics)

We are now coming to an end of the rational choice series. Not without reason is this my favourite theory to explain human behaviour; RCT is an integrated causal theory of (social) action. Integrated means that it can be easily connected with insights from other sciences, such as biology, neuroscience and psychology. After all, an individual actor is nothing else than a macro phenomenon compared to the micro phenomena of their biology, neuronal networks and personality shaped over time. It is a causal theory (and as a former natural scientists I *love* causal explanations), since it looks under the surface of the macro phenomenon to analyse the processes which led to its existence. I hope I could spark at least a little appreciation for this theory in you too :).

Just before I thought there could be nothing better than RCT I stumbled upon synergetics. Sounds a little esoteric, but it is actually a meta theory of change and transformation processes. Okay, still sounds esoteric if I put it like this. But, what if I tell you that it’s based on physics? Sounds more convincing? Did you notice that I included examples of the natural sciences in this article? While RCT can be seen as an application of synergetics, concerned about the emergence of social phenomena, synergetics is concerned about the emergence of any phenomena, from natural to social ones. Turns out that these processes are qualitatively no different from each other! Fascinating, isn’t it?

Dig into the synergetics series!

References [1] Esser, H., (1999), “Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 1: Situationslogik und Handeln“, Campus Verlag Frankfurt/New York, DOI: 10.1007/s11577-001-0109-z [2] Coleman, J.S. (1990), “Foundations of Social Theory“, Cambridge, Mass., and London [3] Esser, H., (1999), “Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 2: Die Konstruktion der Gesellschaft“, Campus Verlag Frankfurt/ New York

Navigate through the episodes of the special theme The Science of Human Behaviour here:

Table of Contents

- Introduction to The Science of Human Behaviour

- Motivation: Research shows that there are 5 different types of motivation. Especially the aggregate forms – autonomous vs. controlled motivation – have a different impact on our well-being.

- Decision Making: Rational Choice Theory explains how we make our 35000 daily decisions and how social phenomena arise from our individual behaviour.

- Episode 1: From situation to action

- Episode 1.1: Institutional Norms

- Episode 2: Taking action

- Episode 2.1: Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

- Episode 3: Emergence of Social Phenomena

- Self-Organisation & Transformation: Synergetics – the meta-theory of order transitions – connects the natural sciences with the social sciences and explain what we can change and what we cannot.

- Synergetics-Dictionary

- Episode 1: Physical principles and basics

- Episode 2: The relevance of transformation

- Episode 3: The Agile Organisation

- Episode 3.1: The Synergetic Navigation System (SNS)

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 29th September 2022