Rational Choice Theory: Institutional Norms

Norms … We can all sort of imagine what is meant by that. Rules, which define how we are expected to behave in certain situations; whether within our relationships, school, the work environment or at a public space. In most cases (tens of thousands times daily!), we do not question them and follow those rules without paying attention.

But what the heck are “institutional” norms or “institutions”? In terms of Rational Choice Theory (RCT)[1], institutions are expectations on the compliance with certain rules, which claim binding validity. In other words, institutions encompass rules and norms with respect to how we ought to behave in a certain situation and environment.

There are 3 forms of institutions: norms or rules, roles and social scripts. Roles and scripts contain norms, but also open slots for improvisation. When it comes to roles think of your role as a sibling, friend, child, parent, partner, the role in your job, the role when you are a customer, etc. All these roles come with the expectation that we follow certain (implicit) rules, norms, attain certain goals and improvise at times. Some roles are more pre-defined than others, some we can shape, to some we need to adapt. Scripts are already mentioned in the previous episode. These are routines in our subconscious about how to deal with certain situations; such as ordering a coffee in a café, switching on the coffee machine first thing in the morning or driving a car. Scripts are based on our socialization within our society (including our up-bringing) and past experiences which reinforced/ adapted a particular script. Most of our 35000 daily decisions and actions are based on roles and their related scripts. And most of the times we comply with the rules and norms at play – whether this is traffic rules, fulfillment of our job role, or showing normative behaviour in a social setting.

Sounds a bit like we are all robots, stupidly following the scripts that were “programmed” into us by our social environment? Not quite … We are always free to choose against acting in accordance with an institutional norm. Then why do we mostly comply with rules and role expectations? Well, it turns out that in most cases, compliant behaviour is the *rational* thing to do.

The 3 functions of institutional norms

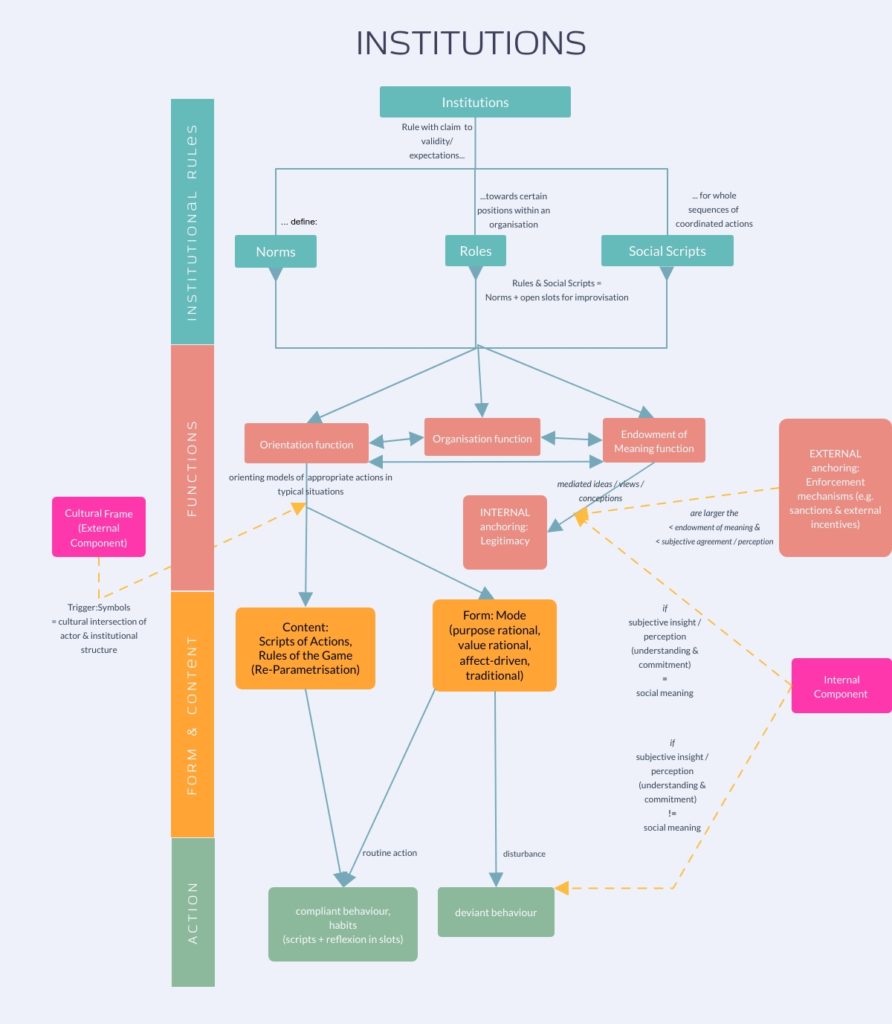

This is because institutions are not there to turn us all into marionettes, following some grand scheme of somebody in power, but they do actually have 3 important functions (Fig. 1) which make all of our lives simpler:

- The orientation function

By setting the rules for what is appropriate behaviour and defining what are desirable goals, institutional norms give an actor a sense of orientation. - The organisational function

Because actors can usually rely on others following the same rules, institutional norms bring order in the otherwise not comprehensible and navigable social situations. This is also how institutional norms parametrise a situation. As opposed to non-social situations (so-called parametric situations), where an actor is “only” exposed to nature, social situations entail a double contingency. This means that an actor, in order to attain a goal, needs to anticipate the actions of others. By prescribing and restricting possible patterns of behaviour, institutional norms virtually reduce the double contingency to a simple one. For example, we “know” that this car is going to stop at the red light so we can continue to cross the street without the fear of being run over. We trust that the roof above us is not going to collapse, because it was built according to architectural standards, which ensure stable statics. - Endowment of meaning function

By defining what is “good”, what is “bad” and what is “admirable”, institutional norms endow actions with meaning. Meaning is entirely socially constructed (such as our labels). Institutional norms and cultural frames are ways of giving meaning, with which a larger population of people can identify themselves with in order to work or live together. Take money, for example: money is an institution that we all believe in and which has a big influence on our daily lives, on what we aspire and what we define as successful.

In summary, institutional norms help us navigate our complex society on a daily basis and trust others, without using too much of our brain power, since we incorporated these rules and norms into our subconscious. Normative or compliant behaviour is *rational* in the sense that they help us in the economic use of our brain power. For example, as an experienced driver, think back to the times when you learned driving and how exhausting it might have been to pay attention to all the traffic rules and signs. Today, driving likely does not cost you much energy anymore (all the “assholes” on the street aside), because it has become a routine. Normative behaviour therefore frees up brain space for the less mundane things in daily life, such as creativity (in your job), the choice of what you want to eat, reading a book or chatting with a friend.

Without institutional norms our society would be total chaos and most of the days you’d be doing nothing else than wondering how you could get some food on the table (and how to protect the table from some invaders into your house). Okay, that sounds a bit extreme and barbaric, but think about it: your house wouldn’t even exist, if there hadn’t been many people involved building it (according to architectural norms so that it won’t collapse the moment you enter) and selling it (according to juridical rules).

So far so good about the mundane compliance of most of our daily life behaviour. What about the much more interesting deviant behaviour?

The internal & external anchor of an institutional norm

When we make around 35000 decisions a day and most of them are compliant, this still leaves a lot of space for deviant actions. Most of this kind of behaviour is minor, such as crossing the street at a red light when there is no one around within a mile of you. Why do we do that? Because we find it stupid to wait around for nobody and if there is nobody to witness, there also won’t be any consequences. Therefore, we seem to deviate from the norm, when we disagree with it (in a certain situation) and/ or when we don’t need to fear/ care about consequences. An institutional norms, thus, has two anchors, which give it its legitimacy: an internal and an external anchor (Fig. 1).

The more actors identify themselves with the meaning the norm provides or agree with the norm’s organisational or orientation function, the stronger the internal anchor of the norm. This agreement/ identification strengthens the internal anchor of an institution. However, for those actors or situations where actors do not agree with the norm, the institution needs an external anchor. The external anchor is comprised of external incentives and enforcement mechanisms, such as sanctions. When an actor disagrees with the norm and the sanctions are lower as compared to the gain of not following the norm, the actor may shift from compliant to deviant behaviour. In other words, when I disagree waiting at the red light, because there is no one around to wait for anyways, and I also do not spot a policemen, I cross the street, because the gain of time is higher than the sanction I can expect. Most of these kind of minor deviances are also subconscious routines, which do not take careful considerations, involving heaps of brain power.

(This figure was created by me and is based on [1])

While this and the previous episode discussed mainly the majority of our decision making which is subconscious and follows routines, in the next episode we will eventually dig into making conscious decisions (whether normative or deviant), which usually cost us more cognitive resources.

References [1] Esser, H., (2000), “Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 5: Institutionen“, Campus Verlag Frankfurt/New York, DOI: 10.1007/s11577-001-0112-4

Navigate through the episodes of the special theme The Science of Human Behaviour here:

Table of Contents

- Introduction to The Science of Human Behaviour

- Motivation: Research shows that there are 5 different types of motivation. Especially the aggregate forms – autonomous vs. controlled motivation – have a different impact on our well-being.

- Decision Making: Rational Choice Theory explains how we make our 35000 daily decisions and how social phenomena arise from our individual behaviour.

- Episode 1: From situation to action

- Episode 1.1: Institutional Norms

- Episode 2: Taking action

- Episode 2.1: Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

- Episode 3: Emergence of Social Phenomena

- Self-Organisation & Transformation: Synergetics – the meta-theory of order transitions – connects the natural sciences with the social sciences and explain what we can change and what we cannot.

- Synergetics-Dictionary

- Episode 1: Physical principles and basics

- Episode 2: The relevance of transformation

- Episode 3: The Agile Organisation

- Episode 3.1: The Synergetic Navigation System (SNS)

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 26th September 2022