Ambiguity tolerance

In our complex world, we struggle daily with ambivalence (or ambiguity). We want to do our job well, but at the same time we want to pay more attention to our child. We feel Schadenfreude and feel terrible about it. We can’t decide whether gender is a biological fact or a social construct.

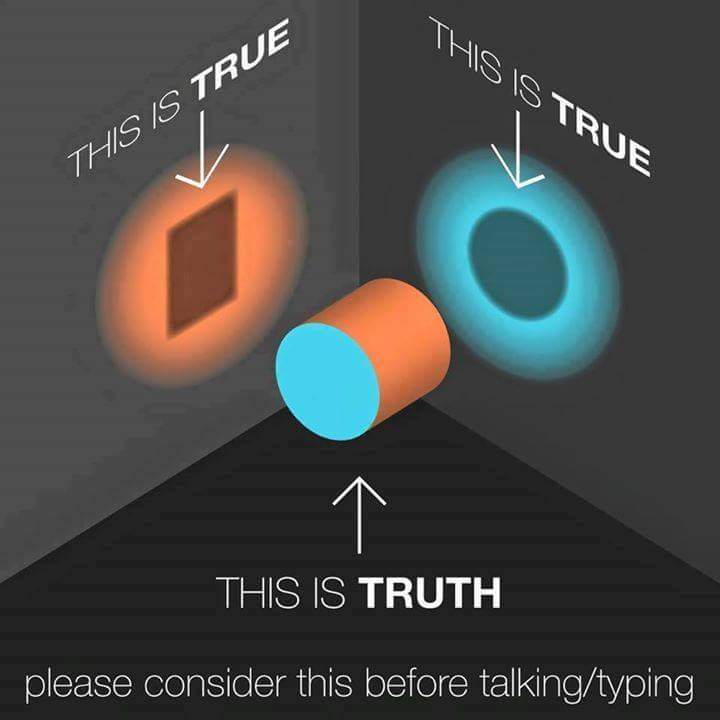

The world is not unambiguous. There are certainly indisputable facts about the physical and the social world. However, at least our perception of these facts and their relevance depend on our situation.

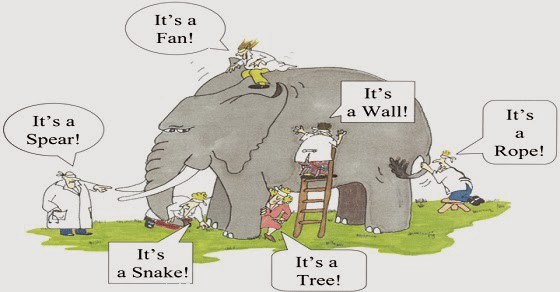

For example, depending on your current focus and biases, you may perceive first a vase or a face when looking at Rubin’s vase. This “reversible figure” contains two patterns (vase/face) that we are most likely to perceive, but not at the same time. We can only perceive one pattern at the time, and yet we can acknowledge that both patterns are present.

Yet, often our socialization does not present us with the proper tools to deal with ambivalence, especially when it comes to our emotions. Often we feel required to choose for one perspective at the cost of the other, instead of acknowledging that they are equally okay and valid. This acknowledgement would, however, give us the freedom to choose which perspective to act on. For example, it is okay and healthy to feel attracted to somebody else while you are in a romantic (monogamous) relationship, but you always have the choice whether or not you want to act on this attraction.

When we do not develop ambiguity tolerance, we run the risk of falling prey to our cognitive dissonances. Often, when we find ourselves stuck between opposing values, expectations or contradicting pieces of information, we tend to harmonise those knowledge- and value systems. In such a case one struggles with the so-called cognitive dissonance. A cognitive dissonance may occur when we experience any clash of pieces of information or values. We experience this dissonance subconsciously and because it makes us struggle, we resort to one of the following psychological patters to allegedly “resolve” it:

- Denial of the incoming information that contradicts available knowledge.

- The re-valuation of one preference in favour for the opposing one.

- Finding arguments for why pursuing one of the preferences will in the long-term also benefit the pursuit of the other.

All three “solutions” are ways to rationalise one’s situation, which is to find a rational justification for one’s behaviour through highlighting some of the arguments for the behaviour at the cost of the arguments against the behaviour.

For example, when we decide to help a friend move, we may have different motivating factors leading to that decision. We may anticipate the friend repaying the favour or we feel like doing it because it’s the right thing to do. To the outside, we would often rationalise our motivations and only present the “noble” one: that we helped because we think it is the right thing to do.

The point of rationalisation is to trick ourselves into denying our feelings of ambivalence and to present a “coherent” solution to the outside. The cognitive dissonance is, however, not resolved, but lingers on in our sub-conscious, waiting to cause trouble.

For example, many years ago I experienced a guy being super crazily in love with me (and I was too!) and yet, he would deny that he had those feelings for me. This was hugely painful for me: Am I just wishful thinking? Am I just not the one (what a bullshit saying btw!)? All over the sudden, I really struggled to trust my own intuition. This was the worst part of my suffering. Only when I got to know about the concept to cognitive dissonance, I understood what was likely really going on: He simply wasn’t ready for a new relationship yet, since his former relationship had just recently ended. Because he couldn’t admit both facts (not being ready, but being in love) at the same time, he denied being in love and this is how he seemingly solved his cognitive dissonance. This caused huge pain to me and also delayed the growth he had to go through at that time. If he had told me that yes, he was in love, but no, he wasn’t ready, I would have been as sad over the loss of him, but I would not have questioned and judged myself the way I did. I was lucky enough that years later he confirmed this theory and admitted that he was indeed in love with me.

Have you recognized this kind of struggle in your own life?

We can only really solve our struggle with feelings of ambivalence (i.e. cognitive dissonances) when we bring them to our consciousness, acknowledge and accept their presence. Only then do these feelings not have the power over us, but we can actually choose what we want to act on. This, in essence, is what ambiguity tolerance means.

Ambiguity tolerance is the capacity to acknowledge seemingly contradicting perspectives or emotions.

– Definition of ambiguity tolerance

Note: Ambiguity tolerance does not mean that anything goes and neither is it an excuse for inconsistencies, such as double standards.

Ambiguity tolerance helps us cope with and grow through crises, such as Covid19-lockdowns or losing loved ones. Ambiguity tolerance makes us acknowledge that equality does not mean to negate our differences, but to acknowledge our equal worth and appreciate our diversity.

Awareness of our ambivalent feelings and exercising tolerance for them is often easier said than done. In order to navigate through our complex daily lives, we strive for clarity and reducing the complexity of situations we encounter. This is absolutely necessary to function in our society. However, we should be aware that any filter we apply to our perception only virtually reduces the complexity of the situation and there are many more valid points of view. Cultivating this awareness and a resulting tolerance for ambivalence is a key competence to successfully (and more joyfully) navigate through our VUCA world.

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 19th October 2022