Synergetics: The relevance of transformation

“Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

– Serenity Prayer

the courage to change the things I can,

and wisdom to know the difference.”

How badly we sometimes wish for this form of wisdom in our daily lives? How often have we picked battles which lead to nothing? How often have we spent energy on doing things differently, and yet we fall back into old patterns? Synergetics delivers answers to the question on how we *can* know the difference – namely through understanding how change comes into being in a self-organised system.

In the previous episode on synergetics we went through its key principles, synergetics’ foundation in physics and explained how self-organisation comes into being. This episode puts these transformation processes under the microscope.

Self-organisation denotes the spontaneous (i.e. not centrally controlled) formation of order in complex systems[1], such as for example the human brain or an organisation. Order is characterised by pattern formation. What is pattern formation?

Perception: A Construction of Patterns

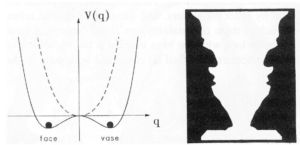

In order to illustrate the process of pattern formation, take the example of our perception and thought. A suitable demonstration of pattern recognition is given by reversible figures – these are images that lead to spontaneous pattern changes in our perception. Commonly known is, for instance, Rubin’s vase (Fig. 1); this is an image where the minds switches between perceiving the foreground (vase) and the background (faces).

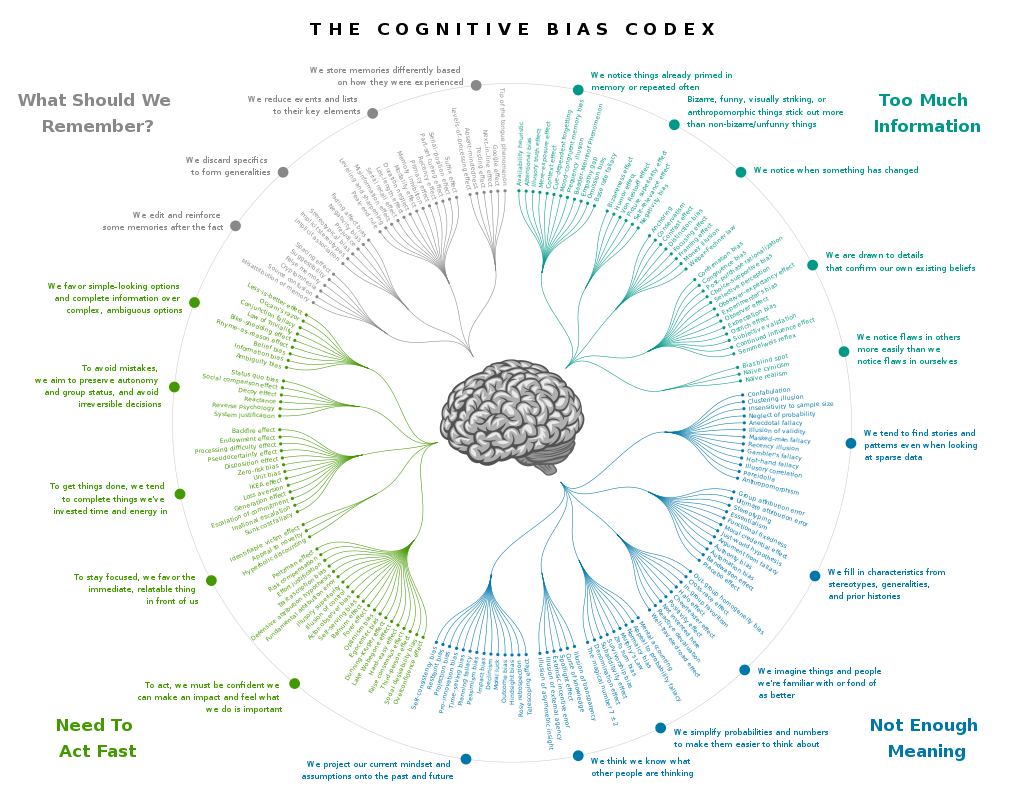

By means of synergetics, we can describe what happens during such pattern changes. On basis of previously learned patterns, focus parameters and (cognitive) biases, one or the other image manifests in our perception[1]. The role of previously learned patterns is obvious; who has never seen a vase (or a similar container), will also not perceive one. If one has just recently put flowers into a vase, one would likely be biased into perceiving the vase before the faces. Biases/ prejudices and learned patterns therefore influence our attention and focus. Moreover, we may also steer our attention more consciously: we are able to let our perception switch between the two patterns.

System States illustrated as Potential Wells

Source: me 😉

This perceptual process can be formally described by a so-called potential well. This is a term from physics and illustrates the region around a local minimum of the potential distribution of a system. The illustration draws on the imagination of a body in a gravitational system (e.g. the earth). The simplest example is a U-shaped potential well (Fig. 2). Such a potential well requires a massive amount of energy for the object (in this case a ball) to reach the edge of the well. Thus, in the case of a U-well, we are dealing with a particularly stable and rigid state.

In synergetics parlance, recognised patterns (e.g. vase/face) “are system states that can be identified with the bottom of the potential well”[1:p.181].

Refer to Fig. 3 for an illustration. This image shows a W-shaped potential well, where one bottom represents the perception of the vase, and the other the perception of the face. We may only recognise one percept at a time, “which presents itself as coherent, distinct gestalt”[1: p.28]. The ball, which is either located in one or the other valley, corresponds to the order parameter. In the simplest case (as in Fig. 3) we are dealing with a completely symmetric potential well. Thus, the probability to perceive a vase is the same as perceiving a face. In the individual case this, naturally, doesn’t have to be this way. For example, a valley may be deeper or wider than the other; Depending on certain experiences, biases/ prejudices, etc., it may be easier to perceive one pattern than the other. An incomplete or not yet recognised pattern, may be depicted as a ball located on a slope[1].

Order Transitions

At the perceptual change, the ball jumps from one valley to the other. Order transitions are often erratic and discontinuous, “whereby the interphase of uncertain oscillation is hardly noticeable”[1: p.28]. In between the two valleys, there is a very unstable point, where at first we do not perceive any pattern. But not for long – we are talking about split seconds. These kind of extremely unstable states are especially interesting with respect to self-organisation, because random fluctuations of the ball’s movement (order parameter) can decide in which of the valleys they ball will end up. This means that the figurative getting out of bed on the wrong side may be as impactful on a state change as a rational argument. Especially interesting is that “true randomness”, i.e. quantum fluctuations, can potentially play a big role at such unstable system states. These “instability points within a system formation”[1:p.289], thus, open up the space for quantum fluctuations to have an impact on a macroscopic level. One may therefore conclude that these instability points correspond to Schrödinger’s Cat! In summary, randomness, as well as the system history (learned patterns, focus/ attention, biases/ prejudices) play a role in order formation, such as pattern recognition.

Instability points within a system state, such as pattern recognition or an initial judgement of a person/ situation, are the Schrödinger’s Cat of our daily lives; A truly random quantum fluctuation may be as influential as the spur of the moment (e.g. incidental emotions) or other subconscious factors, such as biases.

– from a conversation with Dr. Helmut Schöller (Institute for Synergetics and psychotherapy research)

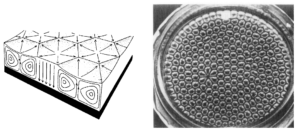

Perception (e.g. pattern recognition) and thought are, as described above, demonstrative examples for the continuous generation of order transitions. Research shows that actually all sorts of system states and patterns can be described by such potential wells. On that point, an illustrative example from physics: the Rayleigh–Bénard convection. This convection describes the following phenomenon: Upon heating up a thin layer of liquid, the fluid develops a regular pattern of convection cells (Bénard cells), which look like hexagonal patterns from above (Fig. 4, right part). Looking at the Bénard cells from the side, one can observe that these cells rotate alternatingly to the right and to the left (Fig. 4, left part). Hence, the pattern emerges from some kind of order.

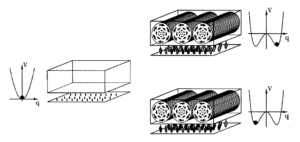

How did this order come into being? I.e. who or what decided which cells turn to the left and which to the right? Look at Fig. 5: Before the heating, the liquid is at rest (left part). This system state is quite stable (U-shaped potential well), since most actions (such as stirring it) will eventually lead back to the initial state of rest. However, heating up the liquid – and thereby changing its control parameter temperature, the potential well transforms to a W-shaped one (Fig. 5, right part). The order parameter (the “ball”) is initially located at the unstable system state at the middle of the W-well, just like in our vase/face-recognition example. Now one convection cell forms earlier than others. This happens for example due to minimal temperature variations in the hotplate or a quantum mechanical fluctuation in the temperature. The highly unstable system state is now very vulnerable to any of such minimal fluctuation. Thus, the order parameter (first convection cell) is kicked into the left or the right side of the W-well, where the left side represents left rotation and right side represents right rotation. Following this event, all other cells are ordered into the alternating rotational directions.

This process is called symmetry breaking; During the heating it was initially as likely that the first forming convection cell will start to rotate left as it was to rotate right. Upon its first movement into rotation, however, it set up the order for all the other cells too for the rest of the process. As I will describe in the next episode, the intentional induction of symmetry breaking is an essential ingredient in transformation processes (such as organisational culture change). Purposeful adaption of control parameters may lead to a transformation of the potential wells and may therefore dissolve deadlocked patterns. A transformation of the potential well opens up the potential for system states which weren’t previously possible. The shape of the potential well of a system, and therefore the possibilities of the system, thus depend on the system’s control parameters.

Adaptive stability requires diverse potential landscapes

Complex systems, such as the human brain or an organisational culture, require rather more-dimensional so-called potential landscapes than the 2-dimensional U- or W-shaped potential wells. However, let’s look at an example for a U-well for a last time. Imagine a human with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). No matter, how many external (coming from others) or internal (coming from oneself) arguments count against the repeated action of washing one’s hands – thus, no matter how high you kick the “ball” – the order parameter will roll back to its bottom at the U-shaped well. This example illustrates why these kinds of extreme forms of system stability are not desirable, but rather too rigid. Hence, (extreme) stability does not necessarily equal desirability. This applies to our psychological states, but also to our social systems, such as organisations. Therefore, the following citation regarding our psychology may be directly translated to our social systems:

“Health is associated with a more flexible order and deterministic chaos. By contrast, illness is rather related to solidified order and/ or chaotic processes without coherent order parameters. The latter makes it impossible to adapt to external influences or environmental changes.”

– [1: p.243; translated from German]

The capabilities of the system states of a healthy mind or a healthy organisation, can therefore be illustrated by a potential landscape. A potential landscape includes diverse forms of wells – none of which are too deep – so as to enable adaptive stability[1: p.28]. Adaptive stability is associated with the systems capability to easily switch between states. In other words, pattern transitions are easily possible. This means that in order for us to keep an open mind and not to get too stuck in certain patterns (i.e. too stable), our “perception and thought operate at the brink of instability”[1: p.28]. This way we are able respond more flexibly to a change from external input.

The formation of order reduces complexity (virtually) and thereby reduces the degrees of freedom of a system, while the degree of effectiveness increases. In other words, when we, for example, have certain routines (i.e. patterns) for certain actions, we are more efficient, because our mind is not concerned with the complexity of the situation, but we act according to so-called scripts (subconscious action plans). At the same time, we strip off some complexity of the situation, which means that we do not perceive things that are not relevant to us. Keeping an open mind makes us capable of appreciating, but also re-evaluating routines. Therefore, as a general rule, it is wise to keep a good balance between order and the openness to discover alternative patterns (such as the act of “unlearning”).

What does all this mean with respect to a transformation process in an organisation?

The equivalent of the brain, which operates at the brink of instability in order to ensure adaptive stability for the human mind, agility in organisations.

Agility requires the acceptance that any complex system, such as an organisation, is self-organised by nature.

– Julia Heuritsch

From this acceptance follows the insight that a central control unit, or top-down delegate measures, are only beneficial to a limited extent and may not lead to the aspired outcomes, but may have unintended consequences.

As we saw above, change processes can – by means of synergetics – be characterised by a transition of the order (parameter) from one well into another (e.g. pattern transition), or by a transformation of the potential landscape itself.

“The former we identify as change, the latter as transformation.”

– The unternehmensdemokraten1

In other words, transformation is associated with a paradigm change; a fundamental transformation of the potential landscape itself. By contrast, change is characterised by the flexible exploitation of alternative, currently perhaps more appropriate wells within the potential landscape.

True agility requires a transformation from our traditional way we look at social complex systems (such as organisations) to an agile mindset.

How can we make use of synergetic’s key principles and therefore, how can we make use of the self-organised character of organisations, with respect to change- and transformation processes? It turns out, that we can derive so-called generic principles[1] from synergetics, which facilitate these processes. These generic principles are the topic of the next episode of this synergetics series.

What can I change and what not: Serenity Prayer 2.0

Last but not least, back to the serenity prayer – how would we phrase this in synergetics parlance? Let’s reflect on the implication of the above described possibility to illustrate transformation processes as the transformation of potential landscapes themselves. Performing this reflection makes it easier for me personally in my everyday life to differentiate between what I can change and what not, and therefore to decide where to best invest my energy. Learning to distinguish a rigid potential well, whose control parameters one cannot influence, from a potential landscape one can affect, is precisely the wisdom addressed by the serenity prayer. Therefore, here my version of the serenity prayer:

“Grant me the serenity to accept potential wells, whose control parameters I cannot change,

–Serenity Prayer in Synergetics parlance

the courage to constructively shape those potential wells, whose control parameters I can influence,

and wisdom to know the difference.”

1 The unternehmensdemokraten (cooperate democrats) is a consulting company specialised in self-organisation and transformation processes in organisations. Thanks to my role there (which I did voluntarily next to my PhD) which involved the development of evidence-based methods to introduce and evaluate New Work, I was able to dig deeper into this field of synergetics.

References [1] Haken, H. & Schiepek, G. (2006, [2010]): “Synergetik in der Psychologie – Selbstorganisation verstehen und gestalten”, Hogrefe; Quotes are translated from German by me [2] Haken, H. & Wunderlin, A. (1991): “Die Selbststrukturierung der Materie”, Braunschweig: Vieweg

Navigate through the episodes of the special theme The Science of Human Behaviour here:

Table of Contents

- Introduction to The Science of Human Behaviour

- Motivation: Research shows that there are 5 different types of motivation. Especially the aggregate forms – autonomous vs. controlled motivation – have a different impact on our well-being.

- Decision Making: Rational Choice Theory explains how we make our 35000 daily decisions and how social phenomena arise from our individual behaviour.

- Episode 1: From situation to action

- Episode 1.1: Institutional Norms

- Episode 2: Taking action

- Episode 2.1: Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

- Episode 3: Emergence of Social Phenomena

- Self-Organisation & Transformation: Synergetics – the meta-theory of order transitions – connects the natural sciences with the social sciences and explain what we can change and what we cannot.

- Synergetics-Dictionary

- Episode 1: Physical principles and basics

- Episode 2: The relevance of transformation

- Episode 3: The Agile Organisation

- Episode 3.1: The Synergetic Navigation System (SNS)

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 4th October 2022

This article was originally written for the blog of the unternehmensdemokraten.