The relationship between maturity and gratification

How is our maturity related to our motivation (i.e. the intent of our choices)? How is our motivation related to gratification (i.e. rewards)? And what does all of that have to do with not only our personal lives, but also with a healthy work environment?

From this recent article, we learned that performance measures inspire us to game the target. We find ways to take shortcuts to success. Hence, performance indicators do not usually lead to loyalty to the cause or the organisation, but foster insecure overachievers.

Performance measures promise external rewards, such as a job promotion or a financial bonus, and therefore motivate us in the shape of external regulation (a form of controlled motivation). Research shows, however, that work environments which tap into people’s autonomous motivation foster the employee’s loyalty, their well-being and their performance.

Autonomous motivation arises when people’s values and beliefs are aligned, and they have the ability to express themselves through their actions, with authority and responsibility for self-determination. Once people are [autonomously] motivated, working towards a purpose and taking responsibility is no longer an issue.

– “Reinventing Organisatzions” by Frederic Laloux [1]

For a quick recap, autonomous motivation is comprised of identified regulation and intrinsic motivation. While the former is doing something because it’s the right thing to do, the latter refers to doing something out of pure curiosity or fun. Most of the popular literature on New Work, such as “Reinventing Organizations”[1], conflate intrinsic motivation with autonomous motivation. However, as we will discover, this distinction is very important because intrinsic motivation and identified regulation basically lie on opposite sides of the of the maturity spectrum.

Motivation and Maturity

With the help of Mark Manson’s beautiful article on “How to Grow the Fuck Up“[2] I relate the five types of motivation to maturity in this section.

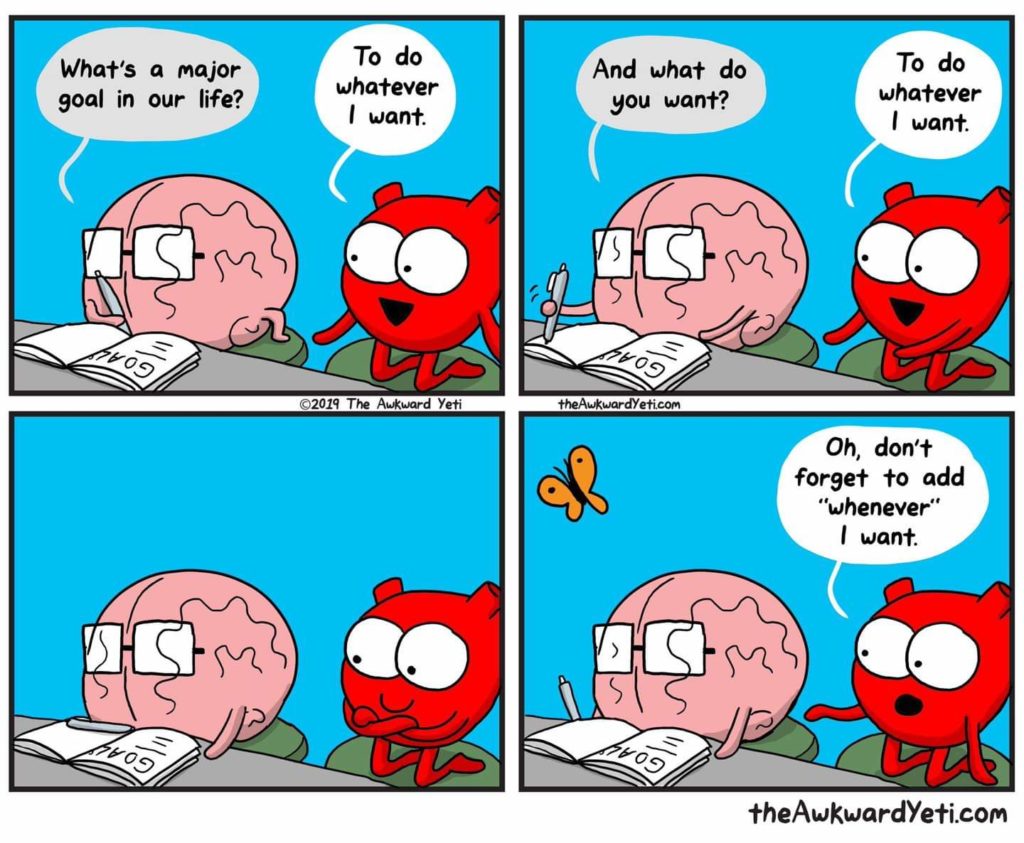

From childhood onwards, we learn to make value judgements of what feels good (e.g. eating ice-cream) and what feels bad (e.g. touching a hotplate). As a child, by following our innocent curiosity to explore the world, we develop a hierarchy of preferences of pleasure and pain. We are fully in being mode and go solely after our intrinsic motivation to do what feels good right now and not do what feels bad right now.

As we grow older, we learn that the consequences of eating the whole bucket of ice-cream (mom shouting at us) may not be worth the short-term pleasure. We learn that there are rules in this world, we learn about cause and effect. Actions have consequences. We substitute our curiosity of exploring with rules & principles that “help us navigate the endless complexity of the world before us”[2]. These rules depend on our socialisation, mainly stemming from our parents and teachers.

Hence, the adolescent brain bases decisions not only on what feels good and bad immediately (intrinsic motivation), but also on what consequences this action will have. Any consideration of consequences, other than immediate pleasure, is related to extrinsic motivation.

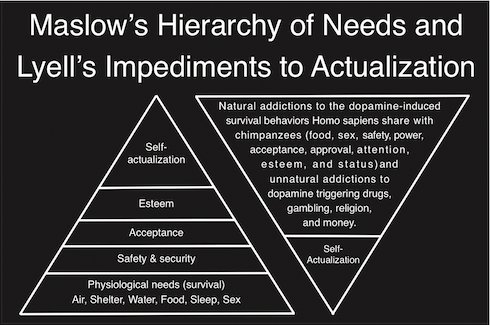

As a recap: extrinsic motivation comprises of external regulation (expecting a reward/ avoiding punishment), introjected regulation (avoiding guilt/shame or expecting to feel pride/ get approval) and identified regulation. The latter – together with intrinsic motivation – aggregates to autonomous motivation (as mentioned above). The former two aggregate to controlled motivation.

– Recap: 5 forms of motivation and their aggregates

As an adolescent we therefore learn to negotiate our own desires with the desires of those around us and that if we play by the rules (compliant behaviour) we will likely be rewarded.

“[…] developing higher-level and more abstract principles to enhance decision making in a wider range of contexts” is “maturity in action”.

– Mark Manson[2] on the stage of adolescence

While this is an improvement in decision making as compared to the impulsive child who only goes after immediate pleasure, there is a weakness in the adolescent approach to life. The adolescent brain only knows intrinsic motivation and calculated trade-off. The adolescent makes decisions based on whether the immediate pleasure is worth the consequence or whether some other action would bring more pleasure/ less pain in the longer term. The being mode is largely replaced by doing mode and most actions are performed in order to get or avoid something.

In today’s society we are usually stuck on this maturity level for the most part of our daily lives.

“While people who navigate the world through bargaining and rules can get far in the material world, they remain crippled and alone in their emotional world. This is because transactional values create toxic relationships — relationships that are built on manipulation. […] This is because, when you view all relationships and actions as a means to an end, you will suspect an ulterior motive in everything that happens and everything anyone ever does to you.”

– Mark Manson[2] on being stuck on adolescent maturity level

By contrast, adulthood – hereafter, in terms of maturity not age – brings identified regulation into the game of decision making. As we mature, we develop another hierarchy of values – one of what is right and what is wrong. As an adult, we realise that an abstract principle, such as telling the truth, is right for its own sake. Identified regulation becomes part of our motivation spectrum. In many cases, it will therefore feel better to adhere to the (ugly) truth than to make up a pretty lie.

“The adult does what is right for the simple reason that it is right.”

– Mark Manson[2] on the capability of an adult to act out of identified regulation

Identified motivation doesn’t mean of course, that doing something for the sake of it being the right thing to do doesn’t get us something out of it. We always choose the action option with the highest utility for us, according to rational choice theory. Therefore, acting based on identified regulation means that we choose the right cause to have more value for us than a pleasurable consequences from the wrong or an alternative cause. The activity in itself has value.

The same, of course, is true for intrinsic motivation, so what’s the difference? When we do something for its own sake, which gives us immediate pleasure, we do it out of intrinsic motivation. When we do something for its own sake, because it feels like it’s the right thing to do, we do it out of identified motivation. In both cases, we are true to ourselves (which doesn’t, however, mean that impulsive instant gratification is necessarily the most constructive thing we can do).

As an adult we may also consciously choose for the external reward (external regulation) or bargaining for validation (introjected regulation) and when we do so consciously, we are also true to ourselves. Often, however, we rationalise our actions, which means that we claim we do something out of the more noble identified resgulation than for the sake of the expected reward. In this case, we are fooling ourselves and others.

“The truth is, it’s hard to detect what level our values are on. This is because we tell ourselves all sorts of elaborate stories to justify what we want.”

– Mark Manson[2] on rationalisation“There’s a difference between telling someone you’re interested in them because that’s what you think they want to hear, and simply telling someone you’re interested in them because you’re freely expressing yourself. The latter is honesty, the former is manipulation.”

– Mark Manson[2] on the difference between controlled and autonomous motivation“An adult will be honest for the simple sake that honesty is more important than pleasure or pain. Honesty is more important than getting what you want or achieving a goal. Honesty is inherently good and valuable, in and of itself. […] And to steal — even if they got away with it! — would make them feel worse about themselves. […] An adult will love freely without expecting anything in return because an adult understands that that is the only thing that can make love real.”

– Mark Manson[2] on the value of honesty

All our choices therefore come down to what we value* – they are a reflection of how we see the world and how we interprete the way it operates. Our maturity is not reflected by whether we choose pleasure or pain, but for what reason we make that choice.

“Adulthood occurs when one realizes that it’s better to suffer for the right reasons than to feel pleasure for the wrong reasons.”

– Mark Manson[2] on maturity

Suffering is an inherent part of life and done right it helps us to grow. When I personally find myself having to make a difficult choice between doing something painful or avoiding this pain, I ask myself what is constructive to do. Thus, especially when it comes to difficult decisions, I don’t distinguish between pleasure and pain, but between constructive (worth my energy/ the cause) and unconstructive (not worth my energy/ the cause).

In summary, as a child we only know intrinsic motivation – the impulsive indulge in immediate pleasure or immediate avoidance of pain. Then we learn that there are consequences of our actions other than the immediate effects and we start to anticipate them; we add external & introjected regulation to our decision making spectrum. On the next maturity level, we are capable of making decisions, because we identify with the value of the activity itself.

Gratification

Now, how is motivation related to gratification? Gratification is basically the perceived reward that we get out of an action. When we act out of intrinsic motivation, we receive instant gratification – the immediate pleasure by doing something we enjoy for the sake of it. When we act based on introjected regulation, we receive the gratification in terms of approval, for example. When we follow our external regulation we get gratification through obtaining some kind of reward. Both of the latter are cases of delayed gratification – although of course the delay may be in some cases shorter (short-term) and in some longer (long-term). Last, but not least, when we act based on our identified regulation we find it gratifying to do the right thing, usually also instantly. All three latter forms of gratification come at the opportunity cost of the instant gratification by following our intrinsic motivation (unless we get rewarded for something we enjoy doing for the sake of it, which comes with problems by its own – see overjustification effect below).

Do you know the marshmallow test? Briefly, in this scientific experiment, children were offered the choice between getting 1 marshmallow immediately or 2 marshmallows if they resist the temptation by waiting for a period of around 15 minutes. Choosing for the latter is, in essence, what discipline is all about:

Forgoing instant gratification for the benefit of the expected (usually larger) delayed gratification.

– Definition of discipline

I personally love tricking myself into pulling through with something by promising myself a reward. I do that by strategically placing an activity that gives me joy after an activity that costs me pain/ stress. That could be saving the special chocolate for after a run. Watching my favourite series after especially stressful days. Or finishing a difficult email right before lunch.

Delayed gratification is basically our carrot dangling in front of our noses. To the benefit of disciplined people, already smelling the carrot (the mere expectation of the reward) releases dopamine, although that may not be to a sufficient level.

As humans, we need the right mix of instant and delayed gratification to have a healthy level of dopamine (the gratification hormone). Together with the other “happy hormones”, we need dopamine to feel cheerful and motivated. If we only go for delayed gratification, we get burned-out. If we only go for instant gratification, we are impulsive, have a high chance to develop an addiction and won’t be able to pursue long-term goals.

Sparking performance in healthy work

Let’s come back to what’s wrong with the current incentive structure at most of our work places and how we can do better.

We have learnt that rewarding solely on the basis of performance measures, fosters insecure overachievers gaming the target (trust me, I once was one of them). Incentive structures may also come with yet another problem; when we are rewarded for something that we do based on intrinsic motivation (given we actually enjoy what we are doing in that moment), we may lose our intrinsic motivation over time and start doing the activity for the external reward. This phenomenon is called the overjustification effect.

In any case, even if it was constructive to reward people for doing something based on intrinsic motivation the work environment can’t always be fun and games and the goal is not to facilitate employees solely following their intrinsic motivation, impulsively like children, but rather responsible and self-determined adults. This is why it is so important to distinguish between intrinsic and identified motivation, although both make up autonomous motivation, which is positively related with employee performance and well-being.

Healthy work environments foster and depend on people who resonate with the company’s purpose & culture, so that their identified regulation is sparked. This is because, when one’s values and beliefs are aligned with those of the company, one feels autonomously motivated to put one’s heart and sweat into the cause. New Work companies encourage employees to express themselves through their actions and to speak up as they encounter issues or have innovative ideas. This also supports the employee’s self-actualisation.

In New Work companies it isn’t the boss who performs individual appraisals and promises incentives on that basis, but peers who give feedback to each other within the team. One isn’t accountable to a boss, but to their peers with respect to one’s commitments that were arranged together. If one is entrusted and empowered to determine what one is capable of doing and when, one is motivated to fulfill the commitment (identified regulation). Constructive peer pressure, therefore taps into identified and introjected regulation of team members, the latter through the peer-based feedback processes. When individual bonuses are replaced by shared profits within the team, one also has the outlook at an external reward, inspiring one’s external regulation. Detaching incentives from the individual makes individualistic behaviour less attractive and takes the focus back on reaching a goal together.

“Workplaces where we feel we can show up with all of who we are unleash unprecedented energy and creativity.”

– [1: p.189]

* I do not mean to say that there is an absolute right or wrong. Nor that there aren’t “bad” rights or “good” wrongs. When extremists find it right to kill people (including themselves) for their cause, we would surely not agree that the cause is a “right” reason to suffer. Extremists have, wat Mark Manson would call bad values. He distinguishes between good and bad values as such: Good values are evidence-based, constructive and controllable. Bad values are: emotion-based, destructive and uncontrollable.

References [1] Laloux, F., (2014), “Reinventing organizations”, Nelson Parker, 1st edition [2] Mark Manson, “How to Grow the Fuck Up”, Blog Article

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 30th October 2022