Impact of Motivation on our Well-Being

Recap: Types of Motivation

The previous episode on motivation described that all our behaviour stems from basically 5 types of motivation. These vary in their degree of internalization – or in other words, how much we internally agree with the action versus how much we “just” do it for the outcome. Aggregating the 5 motivational types according to this distinction, we may end up with 2 types: controlled versus autonomous motivation. Is the action just a means to an end? Then we act out of controlled motivation. Is the action intrinsically enjoyable or do we perceive it truly as the right thing to do? Then we act out of autonomous motivation.

Autonomous versus controlled motivation: Why bother?

For many purposes, this 2-type distinction is sufficient, as research[e.g. 1-3] shows that acting out of controlled motivation has a different impact on us than acting out of autonomous motivation. Think back to the helping-a-friend-relocate example from last episode; the action itself may be the same no matter whether we act based on controlled motivation (e.g. to get a reward or to not feel guilty) or based on autonomous motivation (e.g. because we genuinely enjoy packing boxes or we feel it’s the right thing to do to help a friend in need) – in both cases the outcome is helping the friend move houses. So why bother about the underlying motivation?

Because it makes a difference for us! While the friend got the help they needed, we are impacted differently when we acted based on controlled versus autonomous motivation. As the labels suggest, behaviour based on controlled motivation tends to make us feel that our behaviour is controlled by outside circumstances, while such that is based on autonomous motivation may support a feeling of ownership of our decision making. We therefore tend to feel more self-determined when we act out of autonomous motivation.

Our 3 psychological needs

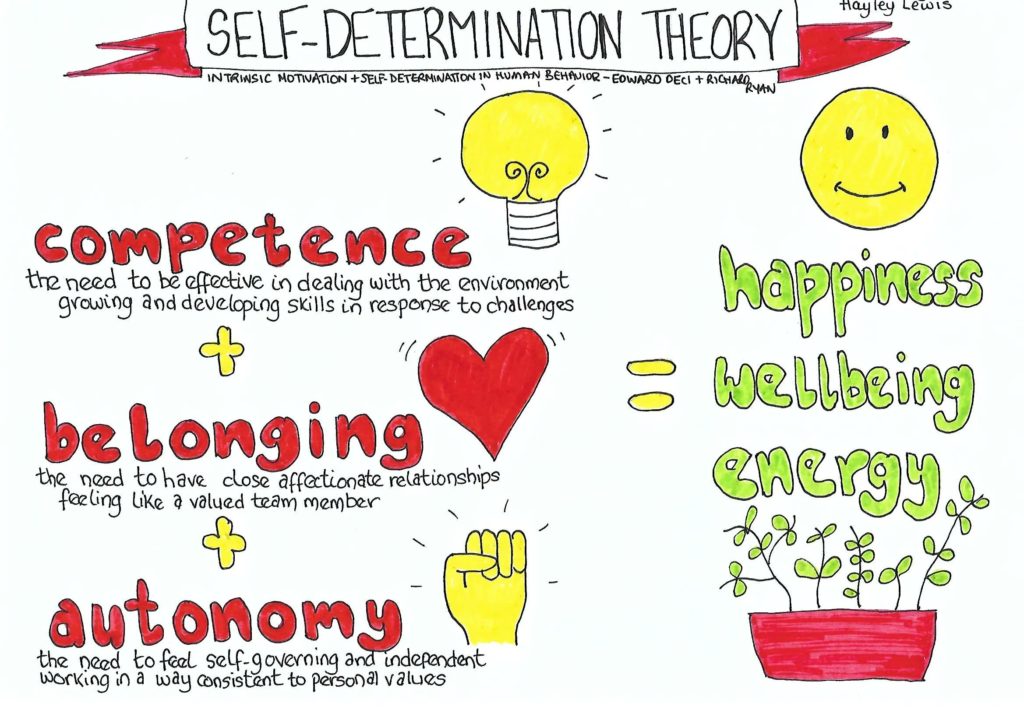

Self-determination theory (SDT) suggests that autonomy is one of our 3 psychological needs[1] in a social setting that make us feel we are the owner of our own lives and valuable in that particular social setting. These psychological needs are autonomy, competence & connection/ relatedness:

Autonomy: People need to feel in control of their own behaviours and goals. This sense of being able to take direct action that will result in real change plays a major part in helping people feel self-determined.

Competence: People need to gain mastery of tasks and learn different skills. When people feel that they have the skills needed for success, they are more likely to take actions that will help them achieve their goals.

Connection or relatedness: People need to experience a sense of belonging and attachment to other people.

Kendra Cherry, MS, is an author and educational consultant focused on helping students learn about psychology; Link to article

Example: The work environment

Our work environment is a very good example for a social setting, which has been under the scrutiny of quite some organizational research with regards to the impact of controlled versus autonomous motivation. This research[2] confirmed SDT’s assumption that autonomous types of motivation are positively related to the satisfaction of our psychological need for autonomy. In SDT, “autonomy means endorsing one’s actions at the highest level of reflection”[3: p.334]. As one of our 3 psychological needs, a higher feeling of autonomy, in turn, generally leads to a better job performance *and* a better well-being. For example, autonomy is related to a higher job satisfaction, commitment, competence, personal initiative & involvement, effort, work motivation and less emotional distress, role stress, absenteeism and turnover intentions[1] .

The prevailing organisational climate is an important factor to foster or inhibit autonomous types of motivation. For example, motivational job design has the potential to compensate for poor leadership and booster motivation levels[1]. In other words, if employees feel in control of the situation (through job autonomy), managerial constraints do not necessarily have negative effects on their motivation. Participative management, which naturally increases perceived job autonomy, is found to have a positive impact on internalisation of the importance of the task, and subsequently leads to a greater intrinsic motivation & performance and less strain[1].

By contrast, controlled motivation, unsurprisingly, is shown to be unrelated to autonomy support and need satisfaction, but related to other types of controlling leadership behaviours[2]. Generally, acting out of controlled motivation is less beneficial to individuals’ optimal functioning than autonomous motivation and may even lead to unwanted behaviour, such as deviant or unethical actions[2].

Conclusion: How can awareness of our motivational reasons help us?

To be the owner of our own life (choices)!

Talking from my own experience, I feel more in doing mode at times that are dominated by making decisions based on controlled motivation and more in being mode in periods where I make more decisions based on autonomous motivation. In other words, I feel more vivacious, when I tend to act based on autonomous motivation. However, life is not a picnic and we cannot always do what we intrinsically feel like. Being an adult comes with chores that we don’t feel like doing in that particular moment or actions to get somewhere or something. Does that mean we are a marionette, because we are not the owner of ourselves when we act based on controlled motivation? Not necessarily!

By being aware of the type of motivation that dominated our decision at present, we take back ownership of our decision making! Acting consciously based on controlled motivation, to get a reward for example, is a choice we make ourselves and therefore – by that conscious act of choosing that type of motivation – we take back ownership.

Try it out :). Next decision you make, ask yourself honestly what was the true dominating reason for taking that action? The more you practice this reflection, the easier it gets to become aware of your motivations. As a next step you can ask yourself, do I want to act based on this reason? If yes, do it consciously – you are the owner of this choice. If no, invest your energy in something else ;). Last, but not least, I would love for you to share these reflections with me in the comments below or a private message :).

Turns out, our motivations and values are not the only factors which influence our decisions, however – are you curious what else our choices depend on? Then continue with the series on decision making …

References [1] Gagné, M.; Forest, J.; Gilbert, M.-H.; Aubé, C.; Morin, E.; & Malorni, A. The Motivation at Work Scale: Validation evidence in two languages. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 2010, 70, 628–646. doi:10.1177/0013164409355698. [2] Gagné, M.; Forest, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Crevier-Braud, L.; van den Broeck, A.; Aspeli, A.K.; Bellerose, J. et al. The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 2015, 24:2, 178-196, DOI: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892. [3] Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 2005, 26, 331–362. doi:10.1002/job.322.

Navigate through the episodes of the special theme The Science of Human Behaviour here:

Table of Contents

- Introduction to The Science of Human Behaviour

- Motivation: Research shows that there are 5 different types of motivation. Especially the aggregate forms – autonomous vs. controlled motivation – have a different impact on our well-being.

- Decision Making: Rational Choice Theory explains how we make our 35000 daily decisions and how social phenomena arise from our individual behaviour.

- Episode 1: From situation to action

- Episode 1.1: Institutional Norms

- Episode 2: Taking action

- Episode 2.1: Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

- Episode 3: Emergence of Social Phenomena

- Self-Organisation & Transformation: Synergetics – the meta-theory of order transitions – connects the natural sciences with the social sciences and explain what we can change and what we cannot.

- Synergetics-Dictionary

- Episode 1: Physical principles and basics

- Episode 2: The relevance of transformation

- Episode 3: The Agile Organisation

- Episode 3.1: The Synergetic Navigation System (SNS)

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 19th September 2022