Rational Choice Theory: Taking action

Recap: The actor’s situation

In the previous two episodes of this decision making series (episode 1 and 1.1), we mainly discussed subconscious decisions, which comprise most of our 35000 decisions of our daily lives. In this article, we cover conscious decisions, which usually take more brain power. We will also go meta: how does one decide between subconscious or conscious decision? Generally speaking: how does one take action?

In episode 1, we discussed what it takes to reconstruct an actor’s situation; determining the 4 influencing factors – the internal component (personality, wishes, values) and the 3 external components (material opportunities/resources, institutional norms, culture) – results in the logic of the situation; the reasons for an action.

This means that the logic of the situation brings about the actor’s motivations. In the series about motivations, we learned that there are 5 types of motivations which can be aggregated to 2 forms; controlled & autonomous forms of motivations. And guess what – autonomous motivational factors relate to those that stem from the internal component (values & personal motives) of the actor’s situation and controlled motivational factors relate to those arising from the 3 external components (e.g. goal orientated behaviour). These motivational factors influence the decisions made by the actor and hence their actions and behaviour. In other words, knowing which type of motivation is most present in a situation helps predicting the behavioural outcome.

This means that an actors’ subjective goal is based on their internal values wishes and oriented around the objective material, institutional and cultural situation. Okay, sounds complicated? How to make a decision with so many factors involved?

Choosing between action alternatives

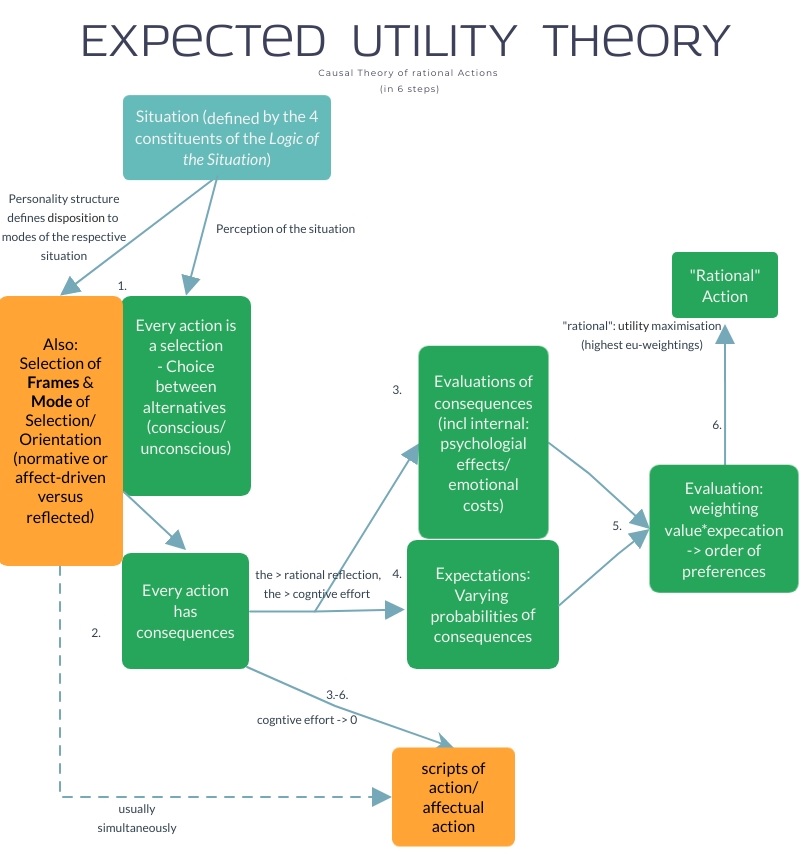

According to rational choice theory (RCT), we now need an action theory to give us the answer! My favourite action theory is the arguably most general and detailed one there is; the so-called expected utility theory (EU-theory; Fig. 1). According to this theory, the actor chooses the one action amongst other alternatives, where the expected utility value is the largest. Expected utility is a combination of the evaluation of the projected result of the action and an expectation with which this result will really occur.

Before we go through the theory step by step; let’s start with a practical, cheesy example[based on 1]:

An actor perceives 3 different alternatives for action based on his situation on a Saturday evening: The first (A1) is to watch a football game with chips and beer cosily on the couch. The second (A2) is to follow his wife’s wish to visit her parents after a long time and bring them a long due birthday present. The third option (A3) is to attend the party meeting of the local association that he has been invited to. According to the EU theory, he is weighing the different costs and benefits (utilities) of all the options. In other words, he is comparing the pros & cons of all the three choices. A1 brings him the biggest joy (sparks his intrinsic motivation), however the costs are that his wife will be angry and uncooperative in the coming days and that he will miss out on the party meeting. He feels that the benefit of the joy does not outweigh the resulting costs. The net utility of this action is therefore negative. The expectation of these pros & cons to realise should he take that action is pretty high (probability close to 100%). If he follows his wife’s wish (A2), he would do so out of the extrinsic motivation to receive praise and recognition from his wife and the parents in law and expects them to be especially accommodating in the proximate future. According to his experience this would also happen with a probability close to 100%. He would, however, lose out on the joy of A1 and his plans to put himself forth as a candidate for chair at the local association (A3). The net utility results in a medium positive outcome. As for choosing A3, he would be able to put forth his candidature, which he has been aspiring for for a long time and his election would give him a lot of satisfaction and honour. His wife would still be disappointed that he wouldn’t visit his parents in law, but she would appreciate his party efforts more than him staying at home for the football game. Despite the opportunity costs of losing out on A1 and A2, he therefore assigns A3 the highest positive net utility. However, the chance that he would get elected is about 10%. How will the man now decide between the 3 options?

Well, A1 is off the table, since the net utility is negative and the expectation of this net utility to occur (him enjoying the evening, but suffering comparatively heavy consequences) lies at around 100% probability. The choice is between A2 and A3 now. The net utility of A3 is higher than A2, but since the probability of the desired outcome of A3 to occur is so much lower than the probability of the outcome of A2, the winner of the highest expected utility outcome is A2.

Now, this doesn’t mean that, in order to make the choice, the man is sitting on his dinner table with pen and paper and writing down this calculation in a very explicit way. He might not even be aware of this calculation that went on in his head. However, this is exactly how we do make decisions. Most of these “calculations” happen more or less subconsciously in our brains, based on intuitive estimations on the likelihood of the occurrence of certain outcomes and their utility. The most important choices (such as what house to buy, what to study, which job to apply for), are on one extreme end of the decision making spectrum, where we often do sit down and make a pro and con list and discuss all our options with the people close to us. We try to bring all relevant factors to our consciousness. Those choices often feel difficult for us and take a lot of mental energy. The mundane daily life actions we undertake, which are orientated mainly around institutional norms and scripts lie on the other side of the spectrum – we hardly notice even making the decision, because they happen subconsciously. In between there are the many decisions, which require a mix of our intuition (subconscious) and our conscious thinking.

Expected Utility Theory

Okay, great, but how do we know how much brain power to invest in the first place? Turns out that this meta-decision on how to decide happens (mostly) subconsciously also according to EU-theory. It’s called choosing a “mode”: we may choose between the more subconscious affect-driven or normative behaviours versus the more conscious reflected behaviours.

Sounds complicated? It’s actually pretty simple, when you look at the whole picture. So if you love abstraction, like me, I delineate here the 6 steps of decision making that happen according the EU-theory[2] (Fig. 1):

1.) An actor perceives being in a situation as defined by the 4 constituents (personality, material opportunities, norms & culture) which may either trigger an action or makes the actor consciously decide to take action. An action always requires a choice between alternatives, whether one is consciously aware of them or not.

2.) Every action has consequences, which may be anticipated or to be avoided.

3.) The actor evaluates those consequences according to their attractiveness (utility). The more factors the actor includes, the more accurate the evaluation. For example, the actor may not only consider the more obvious “goodness” or “badness” of the outcome, but also what kind of psychological costs[2] attaining the outcome will have (e.g. sunk cost effects, framing effects, opportunity cost effects, ownership effects, certainty effects, reference point effects, availability effects, and satisficing).

4.) When assessing possible consequences of an action one essentially makes a prediction. Hence, an outcome can only be attained with a certain probability. An actor therefore needs to assess with what expectation (probability) an outcome may be attained.

5.) Both, the attractiveness and the probability of the occurrence of the outcome play important roles in choosing which action is the most attractive to take. In mathematical terms, the product of both factors determine the expected utility of an action. The higher the expected utility, the better the action. Note, that utility as defined here is something entirely subjective; the same outcome may have an entirely different utility for different actors, as it depends on their respective situations.

6.) The actor performs the action with the highest expected utility.

Often, critics of RCT voice their concerns that these 6 steps are too cognitively demanding as to happen in practice at every action a human takes. Indeed, that is true. However, consciously exercising through all 6 steps is only one mode of selection of many others. This reflected mode requires the most cognitive effort an is usually chosen, when important decisions with long lasting consequences have to be taken (like choosing a job, what to study, which house to buy). Other modes, like the normative mode (norm compliant) or the affect-driven (in everyday speech “irrational”) mode do not require such cognitive efforts and allow for a shortcut through so-called “scripts” (see Fig. 1). As a reminder, scripts are pre-defined instruction manuals of how to act in certain situations on the basis of cultural and/ or institutional norms. What selection mode to choose depends on the frame of orientation. The cultural frame consists of the symbols present in one’s current situation that indicates which frame to apply[2]. Frames help defining the situation, since they inform the actor what mode of action and what norms to apply. Hence, by framing the situation, an actor defines what is important or relevant. In other words, a frame of orientation is a model of the situation, often including the definition of certain goals, which gives an actor orientation. The choice of the frame of orientation and the related selection mode is an action like any other, following the EU-theory. Hence, it also follows from the logic of the situation what frames and scripts can be used.

Choosing a mode of more subconscious behaviour, such as affect-driven or normative behaviour, we basically skip steps 3-6 and use our subconscious scripts instead. The cognitive effort is close to 0. Only in situations where it is worth it to spend mental energy, for example when there is no script available to the actor, the actor goes into a reflected mode and performs steps 3-6 separately. This may also happen, when the actor disagrees with the norms or the prescribed scripts (resulting in deviant behaviour). The more reflection with regards to the evaluation of the expected utility, the more cognitive effort we need to spend.

“Rational”: Efficient use of cognitive resources

We have learned from nature that it’s useful to minimize the energy we spend on re-occurring routines. That is what is so beautiful about rational choice theory; it demonstrates that the purpose of most of our choices, which happen subconsciously, is to save mental energy. Even though we’d often label unreflected behaviour as irrational, from an RCT perspective, in many mundane daily life situations it is the most rational thing you can do, to not spend too much cognitive effort.

Therefore, we arrive at a definition of “rational” according to rational choice theory:

There is no such thing as a truly irrational act (even if it may be perceived as such from the outside), because every decision is based on reasons (the logic of the situation). Moreover, it is rational to only spend the least cognitive effort necessary to attain a desired goal, i.e. to use one’s cognitive resources efficiently. In other words, in most cases it is actually very rational, not to invest cognitive resources and follow scripts instead.

– Definition of “rational” in terms of Rational Choice Theory

Since this definition stands in opposition of our daily use of the word rational, which often refers to a high investment of cognitive resources and reflection, I am curious of how this article shaped your view of what is rational behaviour. Did this article support you in gaining insight in human decision making? Perhaps even to have more empathy for other people’s decisions, given that they also have reasons for behaving like they do? Please do share your thoughts in the comments below or via a private message :).

The next episode of this decision making series will illustrate how rational choice theory is capable of explaining how social phenomena emerge from the collective behaviour of many.

References [1] Hill,P.B., (2002), “Rational-Choice-Theorie“, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, ISBN 3-933127-30-0 [2] Esser, H., (1999), “Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 1: Situationslogik und Handeln“, Campus Verlag Frankfurt/New York, DOI: 10.1007/s11577-001-0109-

Navigate through the episodes of the special theme The Science of Human Behaviour here:

Table of Contents

- Introduction to The Science of Human Behaviour

- Motivation: Research shows that there are 5 different types of motivation. Especially the aggregate forms – autonomous vs. controlled motivation – have a different impact on our well-being.

- Decision Making: Rational Choice Theory explains how we make our 35000 daily decisions and how social phenomena arise from our individual behaviour.

- Episode 1: From situation to action

- Episode 1.1: Institutional Norms

- Episode 2: Taking action

- Episode 2.1: Excursion: Deviant Behaviour

- Episode 3: Emergence of Social Phenomena

- Self-Organisation & Transformation: Synergetics – the meta-theory of order transitions – connects the natural sciences with the social sciences and explain what we can change and what we cannot.

- Synergetics-Dictionary

- Episode 1: Physical principles and basics

- Episode 2: The relevance of transformation

- Episode 3: The Agile Organisation

- Episode 3.1: The Synergetic Navigation System (SNS)

Written by Julia Heuritsch | Last edited: 28th September 2022